A detail from a Christmas card bearing the inscription “Glædelig Jul!”. Restaurationen with the first Norwegian immigrants departs from Stavanger in the year 1825. It is unknown when the card was made or by whom, but it is believed to have been created in connection with the centennial commemoration in 1925. The phrase “Glædelig Jul!” is an old-fashioned Scandinavian greeting meaning “Merry Christmas!”

The sloop Restauration

In the summer of 1825, the sloop Restauration departed from Stavanger, Norway. Aboard were seven crew members and forty-five passengers. This voyage is considered the beginning of organized Norwegian emigration to to the United States. After fourteen weeks at sea, they arrived in New York City – their destination – with forty-six passengers. What kinds of historical sources can help us uncover the circumstances surrounding their departure, the long Atlantic crossing, and their arrival in the bustling city?

Before the Journey – Many Traces Are Lost, but Some Remain

Few archival records have been preserved that tell us what the crew and passengers did in the lead-up to the departure of the sloop Restauration. Still, a handful of documents offer glimpses into the practical and administrative preparations that took place.

Restauration was purchased in the spring of 1825 in the town of Egersund and sailed to Stavanger by master Peder Eriksen Meeland. According to customs records, he transported goods for Søren Heskestad – including 20 barrels of Spanish salt and household items such as furniture, bedding, books, and a lathe – as well as two longcase clocks and a clock case for Tosten Madland. The ship docked in Stavanger in early May. About two months later, in early July, Restauration departed for New York with Lars Olsen Helland as master and Meeland serving as first mate.

Several of the emigrants sold property and belongings before leaving. Johannes Stene, considered the principal owner of the sloop, sold a wide range of household items at a public auction about six weeks before he left. Among the more than 100 objects were spinning wheels, flour barrels, pewter plates, chairs, clocks, a tea table, a rifle, a mousetrap, a sermon book, a coffee pot, a mirror, and two pairs of skis.

Less than two weeks later, on June 2, merchant Simon Pedersen Lima – another passenger – sold more than twenty personal items at a similar public auction. It was announced in the same manner as the previous one: by posters displayed on public street corners and by a town crier beating a drum through the streets that morning. Among the items sold were a pillow, a child’s bed, a drop-leaf table, duvet and coverlet, a sofa, and six chairs.

Lima was likely the last of the group to finalize his paperwork. On July 4, he formally renounced his citizenship rights in Stavanger and settled two mortgage debts.. The deed for the property he had sold was officially registered that same day.

Tormod Jensen Madland, a master blacksmith, completed his preparations earlier. On June 20, he appeared before the city court to formally renounce his citizenship, stating that he “intended to leave this place entirely, to travel with his family to North America, and no longer practice his trade here.” He returned his citizenship certificate and was removed from the city register after settling his obligations.

Master Lars Olsen Helland did not renounce his citizenship before departure. As the ship’s commanding officer, he had to coordinate with several public authorities – including customs, harbor pilots, the city council, and naval registration officials – before Restauration could leave port.

The Crew Was Registered

The crew list is dated June 27, 1825, and records a total of seven men: six crew members and the master. They came from Egersund and various parts of the Stavanger region, ranging in age from 15 to 39. The youngest, Jacob Andersen Slauvig, was just 15 years old and listed as a “Dreng,” or cabin boy. The average age of the crew was around 26.

Their roles on board were typical for a small vessel of the time: one master, four able seamen, one ordinary seaman (or “jungmann”), and one cabin boy. The able seamen handled daily tasks on deck and in the rigging. The ordinary seaman was younger and less experienced, while the cabin boy assisted with simpler duties.

The Master, Lars O. Helland, confirmed that he was in command of the sloop Restauration, registered at 18½ commercial lasts(kommerselester), and that he intended to sail for North America. He signed the crew list, confirming that he was responsible for the enrolled crew and pledged to comply with the naval enlistment regulations upon return or upon the vessel’s decommissioning.

On the back of the document is the note “Passerer frit,” indicating that the ship had been cleared to depart. The document was signed by C. K. Kielland on behalf of Captain Lieutenant and enlistment officer Koch.

A Pilot Had to Be Ordered

An entry in the records of the Stavanger chief pilot service, dated June 27, 1825, (attachment no. 189), documents the piloting of Restauration and provides some details about the vessel. It was a sloop – a small, single-masted sailing ship – and its destination was “Niewjork,” or New York. The ship carried no weapons, noted in the log as “without sword,” a standard field in pilot records. A vessel without arms was considered civilian and peaceful.

The record confirms that the ship was registered in Stavanger and that the master was Lars Olsen Helland. The pilot assigned to guide the vessel out of the harbor was Sivert Bech. He was responsible for navigating the ship 2½ nautical miles from the city, likely until it reached open sea. For this service, a fee of 1 speciedaler and 72 skilling was paid, along with 1 speciedaler in mileage compensation. Additional fees were paid into the naval enrollment fund and the pilot’s support fund – systems that helped finance staffing and welfare within the pilot service.

The ship’s draft – its depth below the waterline – was recorded as 7¼ feet, or about 2.2 meters. This measurement is important for two reasons: it indicates how deep the water must be for the vessel to sail safely without running aground, and it gives a sense of how much cargo the ship can carry. The heavier the load, the deeper the ship sits in the water. The draft thus serves as a practical limit for how much a vessel could bear before becoming unstable or unsafe for open-sea travel.

For a ship crossing the Atlantic, this was modest. Restauration was relatively small and light, making it vulnerable in rough seas. At the same time, this type of vessel was typical for coastal trade and small-scale shipping in Norway during the 1800s. That Restauration undertook a transatlantic voyage was not only bold – it was also highly unusual.

Goods Had to Be Declared

A record from the Stavanger customs office shows that Restauration carried a small commercial cargo. The ship was loaded with bar iron, iron plates, and nails – goods purchased from local merchants such as J. Kielland & Søn, T. Thomsen, and Ploug & Sundt. In addition, a crate of four-inch nails was registered, transferred from another vessel and sealed by customs officials. All items were approved with the notation “Passerer frit,” meaning the shipment was cleared for departure.

The weight of the cargo was considerable relative to the size of the vessel. Restauration was a small sloop, and transporting such a quantity of iron across the Atlantic posed a challenge. But the cargo was also a vital part of the journey – it was intended for sale upon arrival in America, providing the Norwegian emigrants with essential start-up capital.

Taken in the 1860s, the image offers a glimpse of the city a few decades after some fifty people boarded Restauration. Taken in the 1860s, the image offers a glimpse of the city a few decades after some fifty people boarded Restauration. At the center of the square, we see the mortepumpen — a public water pump that stood there until the mid-1860s.

Tønnes Stavnem described the pump as follows: Among the things that have disappeared is the old market pump – a double pump enclosed in a shelter, with handles and spouts protruding. Before the construction of the waterworks, the well served as the city’s main water source. Here, especially on summer evenings, maids from across the city would gather with their water buckets on shoulder yokes. Water was drawn in turn. Gallant sailors, craftsmen, and apprentices often helped with the pumping and carrying of water back home.

Crowded Conditions on Board

With a crew of seven and forty-five passengers, conditions aboard Restauration were cramped. The vessel measured around 55 register tons, corresponding to an internal capacity of nearly 155 cubic meters. With 52 people on board, that meant each person had, on average, only about three cubic meters of space. To put that in perspective, it’s roughly the size of a small wardrobe.

When you consider that this volume also had to accommodate cargo, provisions, and personal belongings, it becomes clear just how tightly packed life was during the long Atlantic crossing. It also highlights the physical and health-related challenges they had to endure. To receive permission to depart, it had to be documented that no one carried any contagious diseases.

A Clean Bill of Health Was Required

On July 4, 1825, a health certificate was issued at the Stavanger town hall – a document that proved essential for the sloop Restauration to receive clearance for its long transatlantic voyage. The certificate was recorded in the town register by magistrate Oluf Andreas Løwold, who, in his official capacity, had the authority to certify the health conditions in the city and aboard the vessel.

In the certificate, he declared that the crew and passengers were “not suspected of carrying any contagious disease,” and that no dangerous illnesses were present in Stavanger or the surrounding areas. This was far more than a formality – in an era when fear of epidemics like cholera and yellow fever was very real, such certificates were necessary for gaining entry to foreign ports.

The document served as a kind of guarantee that the ship was not carrying infection. It had to be presented at every port of call, and as it would later turn out, it proved crucial when Restauration arrived in Madeira.

The health certificate from Stavanger town hall is therefore not only a record of the health conditions prior to departure – it also stands as a tangible example of how international seafaring, even in the early 19th century, relied on trust, documentation, and cooperation between national authorities.

The health certificate from Stavanger town hall is therefore not only a record of health conditions prior to departure – it also stands as a tangible example of how international seafaring, even in the early 19th century, relied on trust, documentation, and cooperation between national authorities.

A Stop in Madeira

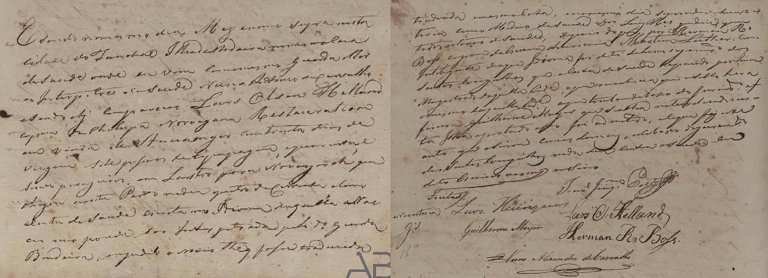

After about a month at sea, Restauration arrived at the port of Funchal, Madeira, on August 4, 1825. Upon arrival, the vessel was inspected and temporarily held by local health authorities. The reason? The ship’s health certificate, written in Norwegian, could not be read by the local inspector. Before new papers could be issued, the document had to be translated.

The translation was carried out by Herman R. Boss, captain of the schooner Martin Luther. Under oath, he confirmed that the certificate had been issued by a magistrate in Stavanger and that he recognized the city’s official seal. His statement was supported by Guilherme Mayer, a naturalized citizen of Madeira, who gave a similar sworn declaration.

It was no coincidence that Boss was asked to assist. According to the records of the Stavanger harbor master, the schooner Martin Luther, under the command of Master Herman R. Boss, had previously visited the city. The vessel arrived in port on January 24, 1823, and departed on April 28, following a three-month stay. The vessel entered port on January 24, 1823, and departed on April 28 following a three-month stay. The schooner was registered in Bornholm, and the master was likely Danish. It seems resonable to assume that he had become familiar with local conditions and people in Stavanger, and that he could read and understand Norwegian. This explains why he was able to translate the certificate and verify the authenticity of the seal.

Only after the sworn statements were given and the certificate accepted was Restauration granted permission to continue its voyage. The episode illustrates how vital it was for documents to be both understandable and recognized by local authorities – and how vulnerable a journey could be if the paperwork was not immediately accepted.

On August 6, the crew list was also officially verified. On the back of the document, just below where C. K. Kielland had signed on behalf of Koch, the Swedish-Norwegian consul in Madeira wrote:

Le soussigné Consul de La Majesté le Roi de Suede et Norowega a Madére atteste et certifie, qu'il n'a pas aucune difference dans le present Role d. Equipage.

A possible English translation could be:

The undersigned, Consul of His Majesty the King of Sweden and Norway in Madeira, hereby attests and certifies that there are no discrepancies in the present crew list.

The consul thus confirmed that the crew was the same as the one that had departed from Stavanger. This was a common practice to certify that no new individuals had been taken aboard and that the crew had remained unchanged throughout the voyage.

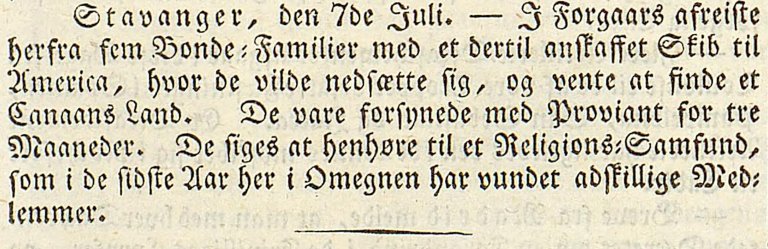

Newspaper Coverage

A few newspaper articles also mention the Restauration. In the spring of 1825, the ship was advertised for sale, and in July of that year, Norske Rigstidende reported on its departure. When the vessel arrived in New York in October 1825, the voyage was covered by American newspapers, which described both the ship and its passengers with a blend of curiosity and admiration.

Sources:

[1] The population figures for 1825 are drawn from: Norway’s Official Statistics (1874). Tabeller vedkommende Folketællingerne i Aarene 1801 og 1825. Ministry of the Interior, p. 76; Norway’s Official Statistics (1856). Folkemængden i Kongeriget Norge den 31te December 1855 and Norway’s Official Statistics (1869). Tabeller vedkommende Folkemængdens Bevægelse i Aarene 1856-1865. Ministry of the Interior."/]

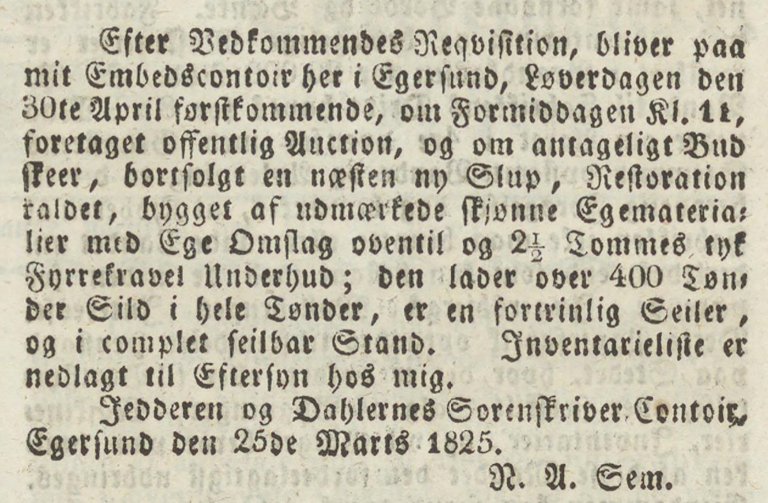

Restauration was announced for sale at a public auction in Egersund in the spring of 1825

(Also published on March 30 and April 6)

One possible translation could be:

At the request of the interested party, a public auction will be held at my office in Egersund on Saturday, April 30, at 11 a.m. Should a suitable bid be offered, a nearly new sloop named Restoration will be sold. The vessel is constructed of exceptionally fine oak, with oak planking above and 2½-inch thick pine sheathing below. She can carry over 400 barrels of herring, is an excellent sailer, and is in fully seaworthy condition.

An inventory has been deposited for public inspection at my office.

– Office of the District Judge of Jæderen and Dalene, Egersund, March 25, 1825.

Signed: N. A. Sem

From a notarial record in the archive of the District Court of Jæren and Dalane, it appears that the announced auction was ultimately not held. Based on the sources we have examined, it is not clear whether the sale of the vessel took place before or after the auction was canceled. The customs ledger contains an entry dated May 4, 1825, stating that the sloop Restauration was to sail from Egersund to Stavanger.

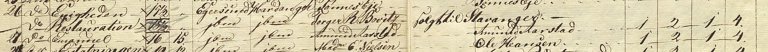

In the 1825 customs records for Stavanger we find the following entry: Number: 119, Type: Sloop, Name: Restauration, Home port: Stavanger, Tonnage: 18½ commercial lasts, Age: Unknown, Built in: Egersund, Principal owner: Johs. Stene, Skipper: Acquired this year from Egersund, Skipper’s name: L. O. Helland, Crew: 1 mate, 2 sailors, 1 boy, Total crew: 4.

In the appendix to the 1825 customs records for Egersund, Restauration is listed as having been built in Hardanger, with Torger R. Bovitz as the principal owner and a note indicating that the vessel had been sold to Stavanger. When the vessel was later registered in the 1825 customs records for Stavanger, the place of construction is given as Egersund, and the new principal owner is listed as Johs. Stene. This may suggest that the most recent place of measurement or reconstruction formed the basis for the updated registration.

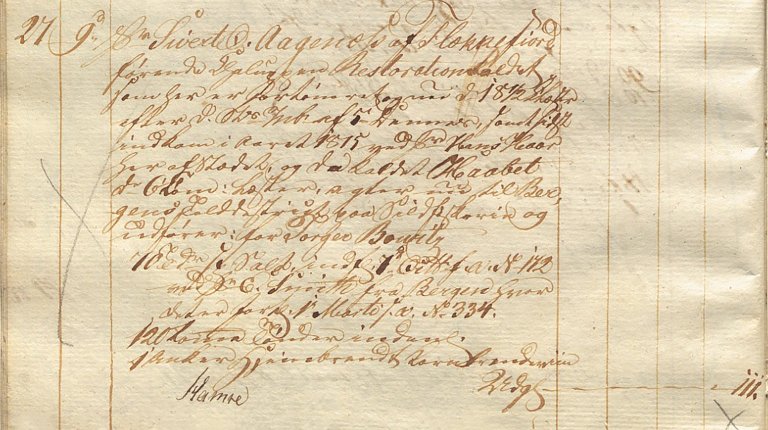

A New Name, a New Mission: The Transformation of Haabet (“Hope”) into Restauration (“Restoration”)

This customs entry from Egersund, dated February 9, 1820, documents a vessel that underwent both a name change and a major rebuild. Previously named Haabet (“Hope”), the ship measured 6½ kommerselester (a traditional Scandinavian unit of cargo volume). After being rebuilt in Egersund, it was renamed Restauration (“Restoration”) and nearly tripled in size –reaching 18½ kommerselester. It was now ready for herring fishing in the Bergen customs district, captained by Mr. Sivert Aagenæss of Flekkefjord. The cargo included, among other things, 70 barrels of Spanish salt and one anchor of homemade grain spirits. The document provides a clear illustration of how older vessels were repurposed and adapted for new uses.

One possible translation could be:

Sivert Aagenæss of Flekkefjord, commanding the sloop named Restoration, which was newly rebuilt here and now measures 18½ commercial lasts according to the customs office’s declaration of the 5th of this month, and which last entered port in the year 1815 under Mr. Hans Haar of this town, then named Haabet and measuring 6½ commercial lasts, now intends to sail to the Bergen customs district for the herring fishery. He is exporting, on behalf of Torger Bowitz:

- 70 barrels of Spanish salt, imported on October 1 last year, entry no. 172 by Mr. E. Smith from Bergen, where it was declared on March 1 this year, entry no. 334

- 120 empty barrels, domestic

- 1 anker of homemade grain spirits

Signed: Hamre. Export duty: 111 skilling (as lighthouse tax)

Two years later, on May 4, 1822, Torger R. Bowitz appeared at the district judge’s office in Egersund. In a certificate entered into the notarial register, it was confirmed that the sloop Restoration had been built of Norwegian oak and pine in 1819/1820, and that the work had been carried out by master carpenter Niels M. Iversen and carpenter Jacob Clausen. The certificate documented both the materials used and the craftsmen involved, and may have served to make the ownership and construction details publicly known. A year and a half later, the vessel was put up for sale.

Health declarations for vessels arriving at the port of Funchal (1825–1828)

[Folio 42:]

And on the same day, month, and year as above [August 6, 1825], in this city of Funchal, Island of Madeira, at the same Health Office, where I arrived with the same chief health officer and the health interpreter Nuno Antonio de Carvalho, there appeared Lars Olsen Helland, captain of the Norwegian sloop Restauration, arriving from Stavanger after a thirty-day voyage, with seven crew members and forty-five passengers, in ballast. The vessel had arrived at this port on the fourth of the current month. Since the health certificate was written in the language of that nation, it could not be interpreted by the said health officer, and the ship was held until the document could be translated.

[Folio 42 verso:]

That same day, the certificate was translated, and an inspection was carried out by the health physician Dr. Luis Henriques, who stated that all were in good health. Following this, Herman R. Boss, captain of the American schooner Martin Luther, who understood the language, declared under oath on the Holy Gospels that the health certificate had been issued by a magistrate of that city and that he recognized the seal as authentic. This statement was also affirmed under oath by Guilherme Mayer, a naturalized citizen of this island. Based on these declarations, the certificate was accepted, and I drew up this official record, which was signed by all parties. Under oath on the Holy Gospels, no objections were raised regarding the health status. I, the undersigned clerk, wrote and signed this record.

[Signatures:]

Freitas

Joam Joaquim Pestana

Luiz Henriques

Lars O. Helland

Guilherme Meyer

Herman R. Boss

Nuno Alexandre de Carvalho

[In the margin:] During the inspection G.s [?]

Transcription from Portuguese by historian Bruno Abreu Costa, of the Regional Department for Archives, Libraries and Books and the Center for Atlantic History Studies – Alberto Vieira.

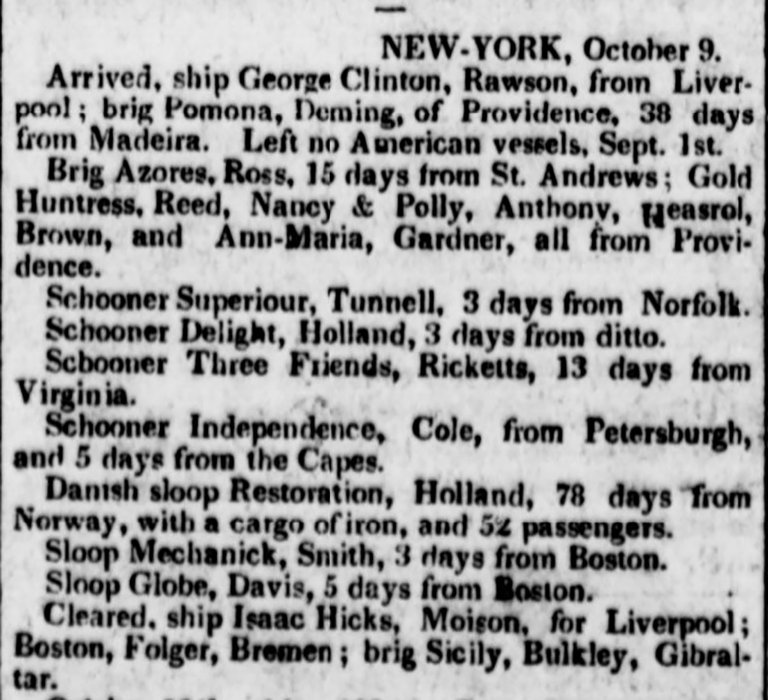

Arrival in New York

On October 9, 1825, the Norwegian sloop Restauration arrived in the port of New York after a long and demanding three-month voyage from Stavanger. On board were Norwegian emigrants hoping to begin a new life in America. The ship also carried a small commercial cargo – about 20 skippund (an old Norwegian unit of weight, roughly 160 kg or 350 pounds each) of wrought iron – intended to be sold upon arrival to help fund their new start. The vessel was captained by Lars Olsen Helland and, according to official documents, was owned by Johannes Steen of Stavanger. But what was meant to be a hopeful new beginning quickly turned into a legal challenge.

A Ship Seized: The Steerage Act in Action

In a letter dated October 15, 1825, addressed to the Royal Norwegian Government’s Department of Finance, Trade, and Customs in Christiania, the Swedish Norwegian consul in New York, Henry Gahn, reported that Restauration had been immediately seized by U.S. customs authorities. The reason: the ship was carrying far more passengers than allowed under the Steerage Act of 1819. This was the first federal law in the United States to regulate conditions aboard passenger ships. Among other provisions, it limited the number of passengers a vessel could carry based on its tonnage. It also required captains to maintain passenger lists and submit them to customs officials upon arrival.

Under the law, a ship could carry two passengers for every five U. S. tons. Restauration was measured at 55 tons, which permitted only 22 passengers – not 45. One child was even born during the voyage.

No Room for Discretion

In his letter, Gahn expressed frustration that the law allowed no room for discretion. Neither he nor the American officials had the authority to intervene on behalf of the ship’s owners. He described how the customs office was “truly troubled by this unpleasant necessity to proceed according to the law” – in other words, they regretted having to enforce the law so strictly, but had no choice. Gahn noted that the value of the vessel barely covered the costs of seizure and legal proceedings.

Still, he mentioned that the customs director in New York – “the Director of the local Customs House” – had generously offered to assist with a petition to the U.S. Department of the Treasury in Washington. Gahn described this offer as “noble,” but made it clear that the process would be both formally complex and financially burdensome. He emphasized that “no official, regardless of rank, can act against or beyond the clear provisions of the law.”

Sympathy and Public Attention

The letter also offers insight into the local reaction. Gahn reported that the Norwegian emigrants had inspired a degree of sympathy for their “boldness and unusual character.” He stressed that he would do what he could to assist them, but also had a duty to ensure that the ship did not continue operating with documents that failed to meet the formal requirements of U.S. law.

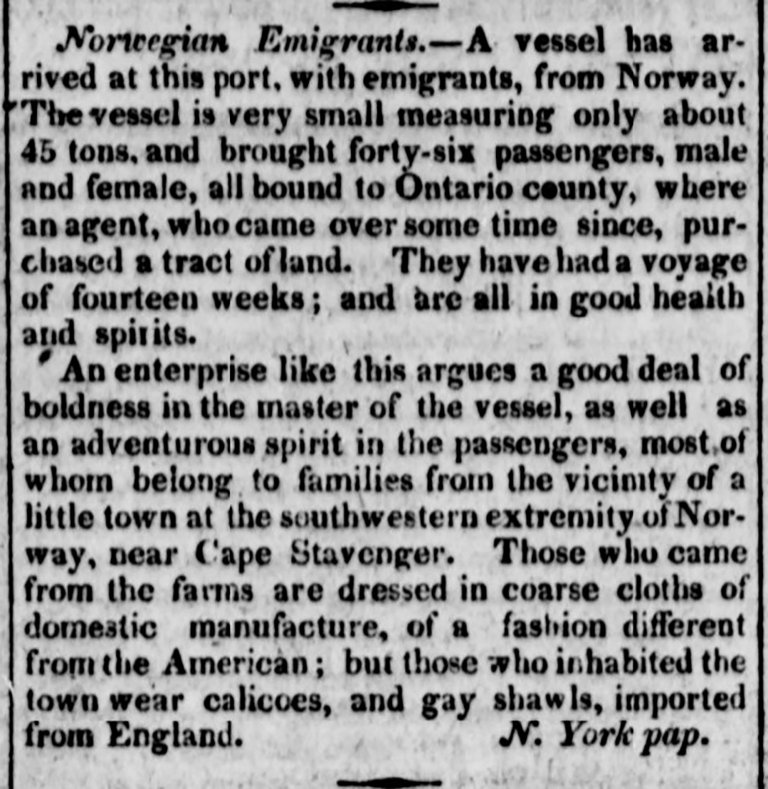

Press Coverage in the United States

Gahn also mentioned that he had enclosed a newspaper clipping from a local paper reporting on the incident. While some of the details were inaccurate, he believed the article gave a generally fair account of the situation. The Rhode-Island American and Providence Gazette reprinted the story on October 18, 1825, citing another newspaper as its source.

Norwegian Emigrantes. - A vessel has arrived at this port, with emigrants, from Norway. The vessel is very small measuring only about 45 tons, and brought forty-six passengers, male and female, all bound to Ontario ceunty, where an agent, who came over some time since, purchased a tract of land. They have had a voyage of fourteen weeks; and are all in good Health and spirits.

An enterprise like this argues a good deal of boldness in the master of the vessel, as well as an adventurous spirit in the passengers, most of whom belong to families from the vicimty of a little town at the Southwestern extremity of Norway, near Cape Stavanger. Those who came from the farms are dressed in coarse cloths of domestic manufacture, of a fashion different from the American; but those who inhabited the town wear calicoes, and gay shawls, imported from England. N. York pap.

Preparing Norway for American Regulations

Henry Gahn concluded his letter by reminding the Norwegian authorities that, earlier that year in April, he had sent a collection of documents to Norway via the Bergen merchant Mr. Keutel. Among them were the latest U.S. customs tariff and several current laws governing trade and navigation. His intent was to help prepare Norway for the legal and logistical challenges that might arise when Norwegian ships and sailors encountered American regulations.

Two Newspaper Reports from October 1825

In the Rhode-Island American and Providence Gazette, the Restauration was described as “Danish sloop Restoration, Holland, 78 days from Norway, with a cargo of iron, and 52 passengers.”

The Steerage Act

The Steerage Act – officially titled An Act regulating passenger ships and vessels – was a U.S. law passed on March 2, 1819. It regulated conditions for passengers traveling in steerage, the lowest and least expensive class aboard ships. These were often emigrants traveling under cramped and modest conditions.

The law required, among other things:

- that captains keep passenger lists,

- that sufficient food and water be provided,

- and that authorities be notified upon arrival.

It was an early attempt to improve the safety and health of emigrants, and it became especially relevant in the case of the ship Restauration, which was seized in New York in 1825 for carrying more passengers than allowed based on the ship’s size.

The introduction reads: Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That if the master or other person on Board of any ship or vessel, owned in the whole or in part by a citizen or citizens of the United States, or the territories thereof, or by a subject or subjects, citizen or citizens, of any foreign country, shall, after the first day of January next, take on board of such ship or vessel, at any foreign port or place, or shall bring or convey into the United States, or the territories thereof, from any foreign port or place; or shall carry, convey, or transport, from the United [States], or the territories thereof, to any foreign port or place, a greater number of passengers than two for every five tons of such ship or vessel, according to custom-house measurement, every such master, or other person so offending, and the owner or owners of such ship or vessels, shall severally forfeit and pay to the United States, the sum of one hundred and fifty dollars, for each and every passenger so taken on board of such ship or vessel over and above the aforesaid number of two to every five tons of such ship or vessel; to be recovered by suit, in any circuit or district court of the United States, where the said vessel may arrive, or where the owner or owners aforesaid may reside: Provided, nevertheless, That nothing in this act shall be taken to apply to the complement of men usually and ordinarily employed in navigating such ship or vessel.

Sec 2. And be it further enacted, That if the number of passengers so taken on board of any ship or vessel as aforesaid, or conveyed or brought into the United States, or transported therefrom as aforesaid, shall exceed the said proportion of two to every five tons of such ship or vessel by the number of twenty passengers, in the whole, every such ship or vessel shall be deemed and taken to be forfeited to the United States, and shall be prosecuted and distrributed in the same manner in which the forfeitures and penalties are recovered and distributed under the provision of the act entitled "An act to regulate the Collection of duties on imports and tonnage".

Sec. 4 And be it further enacted, That the captain or master of any ship or vessel arriving in the United States, or any of the territories thereof, from any foreign place whatever, at the same time that he delivers a manifest of the cargo, and, if there be no cargo, then at the time of making report or entry of the ship or vessel, pursuant to the existing laws of the United States, shall also deliver and report, to the collector of the district in which such ship or vessel shall arrive, a list or manifest of all the passengers taken on board of the said ship or vessel at any foreign port og place; in which list or manifest it shall be the duty of the said master to designate, particularly, the age, sex, and occupation, of the said passengers, respectively, the country to which they severally belong, and that of which it is their intention to become inhabitants; and shall further set forth whether any, and what number, have died on the voyage; which report and manifest shall be sworn to by the said master, in the same manner as is directed by the existing laws of the United States, in relation to the manifest of the cargo, and that the refusal or neglect of the master aforesaid, to comply With the provisions of this section, shall incur the same penalties, disabilities, and forfeitures, as are at present provided for a refusal or neglect to report and deliver a manifest of the cargo aforesaid.

The captain was specifically required to report:

- the age, sex, and occupation of each passenger,

- the country to which each person belonged,

- and the country in which they intended to settle.

He was also required to state whether any passengers had died during the voyage, and if so, how many. This report and passenger manifest had to be sworn under oath by the captain, in the same manner as required for cargo manifests under existing U.S. law. If the captain refused or failed to comply with the requirements of this section, he would be subject to the same penalties, restrictions, and forfeitures that applied to failure to report and submit a cargo manifest.

Follow-Up from the Consul

In a new letter dated November 1, 1825, Consul Henry Gahn follows up on his earlier reports concerning the sloop Restauration.

He confirms receipt of documents from the Royal Board of Trade in Stockholm (Kongl. Commerce Collegium), including a new maritime ordinance and regulations aimed at preventing illegal imports and exports. These legal frameworks define which vessels are entitled to fly the Norwegian flag and what documentation is required for lawful trade and navigation.

At the same time, he reports on missing documentation for another Norwegian master, John J. Pettersson, and explains that efforts are now underway to obtain and forward the necessary papers.

Ongoing Uncertainty Regarding Flag and Status

Regarding the Restauration, Consul Henry Gahn still had not received any new information from U.S. authorities. He reiterated that the vessel had only been able to claim the old Norwegian flag, raising concerns about whether it met the legal requirements for valid national registration. This could affect its legal standing in international waters. Gahn referred to a specific clause – “Article VI, Chapter XVI, §2, page 431” – in a printed 1823 edition of maritime laws edited by Assessor Danckwardt. At the time, ships unable to document valid national affiliation risked being considered stateless – and thus without legal protection at sea. Gahn clearly understood the seriousness of this issue.

The Real Problem Was the Passenger Count

Still, it’s important to understand that the flag issue alone was not the reason Restauration was seized. As Gahn explained in his earlier letter, the formal cause was the vessel’s violation of the Steerage Act of 1819, which limited the number of passengers according to tonnage. A ship of 55 tons was permitted to carry only 22 passengers. Restauration had 45 – and one child was born during the voyage. This was a clear breach of U.S. law.

A Glimpse of City Life and a Broader Perspective

Toward the end of the letter, the tone shifts. Gahn mentions that he has no further updates to report but takes the opportunity to share a glimpse of life in New York. A major celebration was underway to mark the completion of the Erie Canal. He enclosed the program for the festivities on November 4, suggesting it might be of interest to the ministry in Christiania.

This letter demonstrates Gahn’s diligence and his commitment to keeping Norwegian authorities informed – not only about the specific case, but also about broader developments that could affect Norwegian shipping and trade in America.

On November 24, 1825, Swedish-Norwegian Consul Henry Gahn sat down in New York to write to the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Finance, Trade, and Customs in Christiania (now Oslo). His message marked a turning point in the case: he could now report that the sloop Restauration, which had arrived in New York earlier that fall carrying 45 passengers from Stavanger, had been released by U.S. authorities.

The ship had been detained by U.S. customs for a clear reason: it had carried nearly twice the number of passengers allowed under American law. According to the [glossary word="Steerage Act" wordDescription="Also referred to in several places as the Passenger Act."] of March 2, 1819, a vessel of Restauration’s size – 60 2/95 tons – was legally permitted to carry only 24 passengers. Gahn referenced this law and cited both American and Swedish-Norwegian regulations to explain how the ship had ended up in a legal gray area.

The ship had been detained. Why? It had carried nearly twice the number of passengers allowed under American law. According to the Steerage Act of March 2, 1819, a vessel of Restauration’s size – 60 2/95 tons – was legally permitted to carry only 24 passengers. Gahn referenced this law and cited both American and Swedish-Norwegian regulations to explain how the ship had ended up in a legal gray area.

Released – but Not Cleared

Although the case was now resolved – the U.S. government had waived all fines and fees, and the ship was officially released – Consul Gahn emphasized that the vessel still lacked proper documentation and flag status. As such, it could not be considered seaworthy under Swedish-Norwegian protection in American waters. He warned that the ship might not meet the requirements to be deemed sjøfast, a legal term referring to the right to sail under a recognized national flag. To underscore the seriousness of the matter, he sent a formal warning to one of the remaining stakeholders in New York, along with a Danish translation of the relevant legal provisions.

The Emigrants at the Center of the Case

Gahn’s letter was more than a bureaucratic update – it reflected his personal concern for the Norwegian emigrants. He noted that they had arrived with proper papers and certificates of good conduct, and he had chosen to support them. He also reported that the local community in New York had shown great sympathy, donating clothing, money, and supplies to help the travelers as they continued their journey inland.

A Watchful Consulate

Gahn enclosed a price list and shipping manifest from New York, along with a letter from one of the passengers addressed to a relative in Stavanger, Elias Eliassen Tastad. He asked the Norwegian ministry to take the letter under its protective care. Since the letter was forwarded to its recipient and not officially recorded, this explains why it is not preserved in the archives today.

A Lieutenant’s Letter – and Two Documents from New York

On November 29, 1826, First Lieutenant C. H. Valeur wrote a letter to the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Finance, Trade, and Customs from Fredriksværn. He had recently returned from New York, where the Swedish-Norwegian consul, Henry Gahn, had tasked him with delivering two documents to the Norwegian authorities: a customs declaration and a crew list related to the sloop Restauration.

In his letter, Valeur emphasized that he did not know what had become of the travelers, but assumed the consulate would report further developments.

Documents from the Restauration

The two documents Valeur delivered had been issued in Stavanger during the summer of 1825.

The crew list, dated June 27, shows that the vessel was captained by Lars Olsen Helland of Stavanger. The rest of the crew included:

- Peder Eriksen Meeland, first mate from Egersund, age 31

- Johannes Jacobsen Soledal, sailor from Stavanger, age 39

- Gudmund Danielsen Hugaas, sailor from Hetland district, age 25

- Niels Nielsen Hersdal, sailor from Leeranger district, age 25

- Henrich Christophersen Hervig, deckhand from the same district, age 22

- Jacob Andersen Slauvig, cabin boy, age 15

On the reverse side of the document is a notation from Madeira, dated August 6, 1825, in which the local Swedish-Norwegian consul confirmed that no changes had been made to the crew –meaning the personnel remained the same as when the ship left Stavanger. This was a common practice to document that no new individuals had been taken aboard or substituted during the voyage.

The list was signed in Stavanger by Captain Lieutenant Koch and C. K. Kielland, who added the word “Passerer”– a notation indicating that the document had been approved and the vessel was cleared to sail.

The customs declaration, dated June 30, shows that the Restauration carried iron plates, bar iron, and nails – goods exported by well-known trading firms such as J. Kielland & Søn and Ploug & Sundt. Customs duties had already been paid in 1823 and 1824, and the document was approved by the Stavanger customs office.

Tracing the Journey Through the Archives

The story of the Restauration is not only about the voyage across the Atlantic – it is also a story of preparation, bureaucracy, and the roles played by individuals. While many traces have been lost to time, archival records still remain that help us understand a little more – about the people, the era, and the courage it took to embark on such a journey.

Test Your Knowledge

- Where was the sloop Restauration purchased in the spring of 1825?

- Stavanger

- Egersund

- Kristiansand

- Bergen

- Who transported goods such as salt and furniture to Stavanger before departure?

- Lars Olsen Helland

- Simon Pedersen Lima

- Peder Eriksen Meeland

- Tormod Jensen Madland

- What kind of goods did Restauration bring to America?

- Timber and fish

- Bar iron, iron plates, and nails

- Grain and wool

- Furniture and books

- How many crew members were aboard Restauration (including the captain)?

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- What does the note “Passerer frit” on the crew list mean?

- The ship was full

- The document is approved

- The crew was ill

- The cargo was too heavy

Click here for the answer key and more questions.

This digital exhibition was created by Ine Fintland (Senior Archivist) and Synnøve Østebø (Archivist), in collaboration with Atle Brandsar (Advisor), Hanne Karin Sandvik (Senior Advisor), and Tor Weidling (Senior Archivist). All contributors are employees of the National Archives of Norway.

We also collaborated with Bruno Abreu Costa (Historian at the Regional Archives, Library and Book Office and the Center for Atlantic Historical Studies).

In addition, we received valuable help and support from colleagues at the National Archives: Lars Schanke Aamodt (Advisor), Espen Andersen (Senior Advisor), Grethe Flood (Archivist), Kristian Hunskaar (Senior Advisor), Almina Jazavac (Higher Executive Officer), Janet B. Martin (Senior Advisor), Gerd Mordt (Senior Archivist), Eivind Skarung (Senior Advisor), and Øyvind Ødegaard (Senior Advisor).

The article was originally written in Norwegian and translated into English using Copilot, based on the prompt: “Translate idiomatically for an American audience. The article will be published on the website of the National Archives of Norway. Use terminology appropriate for a U.S. readership, and ensure the language is clear and concise.” The final version was reviewed and edited by Ine Fintland and Kayla Marie Tungodden (Senior Advisor) for clarity and accuracy.