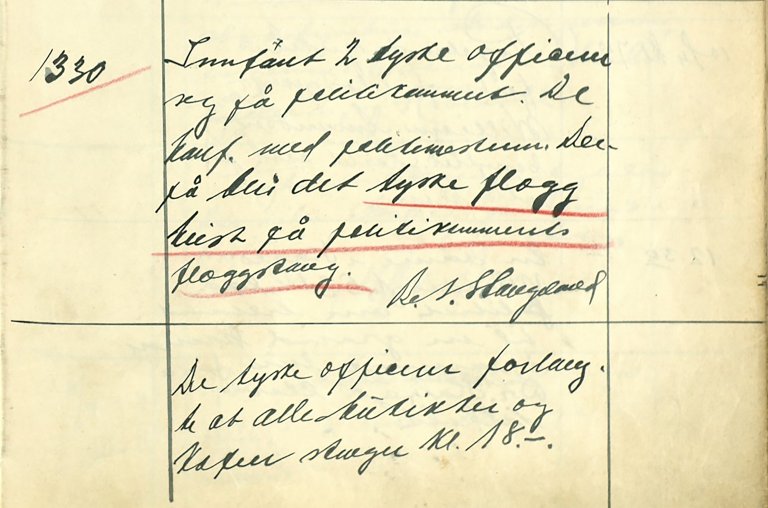

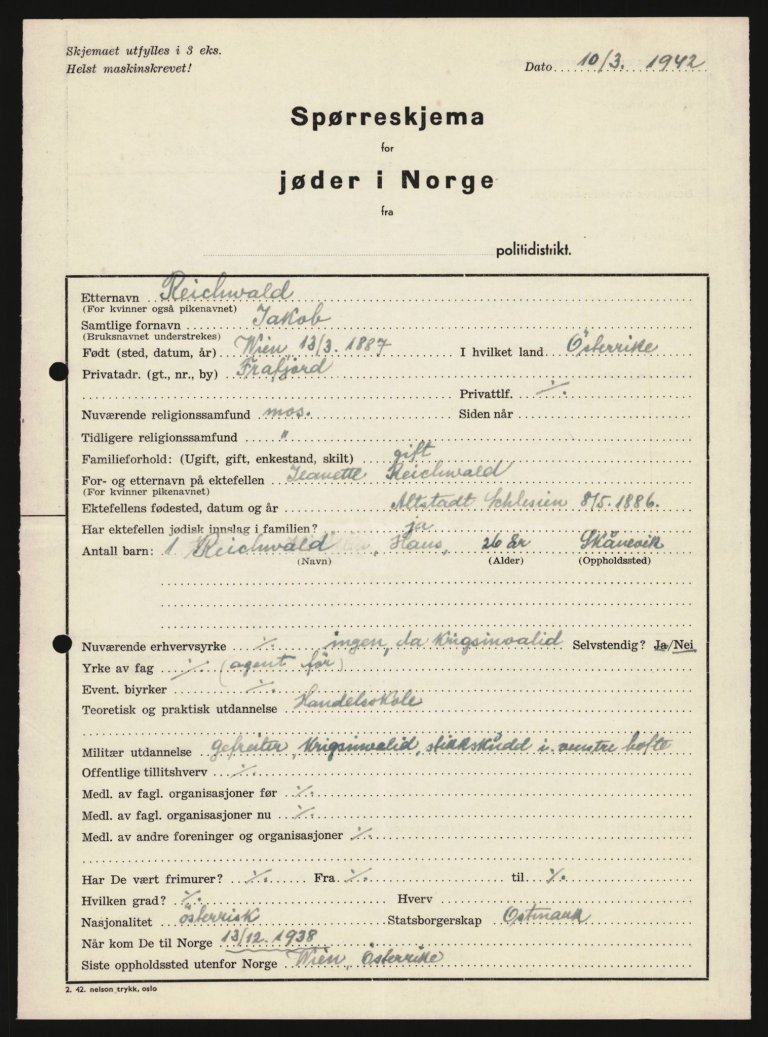

This image shows cropped passport photos from the applications submitted by Jeanette and Jakob Reichwald when seeking permission to reside in Norway.

Jeanette and Jakob Reichwald – Jewish Refugees from Austria to Norway in 1938

After Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938, life quickly became perilous for the country’s Jewish population. Among those seeking refuge beyond its borders were Jeanette and Jakob Reichwald, a married couple living in Vienna. With support from Jeanette’s sister and brother-in-law in Stavanger, they attempted to reach Norway, where their two sons, Hans and Wilhelm, had already been granted residence permits. Rösi and Julius Fein actively reached out to Norwegian authorities and mobilized their personal networks to assist. Through a range of archival records and other sources, we can trace the course of their efforts. These documents shed light on how the family’s shared longing for safety and belonging – between those in Vienna and their relatives in Stavanger – was met with both bureaucratic resistance and moments of human compassion.

Well-Established and Deeply Rooted

In Stavanger, Jeanette’s younger sister Rösi lived with her husband, Julius Fein. When they took the initiative to help Jeanette and Jack – whose birth name was Jakob – apply for permission to stay in Norway, they themselves had already lived in the country for many years. Both had been Norwegian citizens since 1923. Julius had arrived from Lithuania in 1904, and in 1917 he married Rösi Storch from Czechoslovakia.

The couple were professionally active and well integrated into the city’s commercial and civic life. Julius opened the shop Berliner 15-Øre bazar in 1911. From 1922 to 1930, Rösi ran Løkkeveiens Basar A/S. In 1932, they launched Fein's Magasin at Østervåg 15, and six years later they opened a branch in Kristiansand.

They were also active in public life and social causes. Rösi participated in the Stavanger Peace Association (Stavanger Fredsforening), where she founded a youth group dedicated to peace. She gave lectures on her homeland, Czechoslovakia, at both the Stavanger Yrkeskvinners Klubb (Stavanger Professional Women’s Club ) and the Workers’ Temperance Society Frisinn. Another topic close to her heart was the Austrian human rights advocate Irene Harand (1900–1975).

Julius was involved in the Esperanto club La Tagig'o and also contributed to the Fredsforeningen (Peace Association). He gave lectures and wrote several letters to the editor in the 1930s, opposing antisemitism and anti-Jewish hatred. One of these, Nationalism and the Jews, was written in response to an op-ed by Major Tryggve Gran.

The Feins’ engagement was both personal and political, and it is documented in newspapers and archives. They used their position and networks to support, inform, and influence.

A Close Bond

Rösi and Julius, who had no children of their own, shared a close relationship with their two nephews: Hans (born 1916) and Wilhelm (born 1913). During the 1930s, the boys lived with their aunt and uncle in Stavanger while pursuing their education. The older of the two, Wilhelm, was adopted as a foster son at age 23 and remained in Norway. Hans, the younger, returned to Vienna after completing one year at Stavanger elementærtekniske dagskole (Stavanger’s Elementary Technical Day School).

Wilhelm trained as a tailor at the city’s Stavanger tekniske Aftenskole (Technical Evening School). His mother, Jeanette, visited Stavanger shortly before he completed his studies. Both she and her husband, Jakob, had spent three months in the city during the 1920s. It is likely that the sons accompanied them on that trip. Perhaps it was then that the idea of studying in Norway first took root?

In the spring of 1938 Wilhelm received his journeyman’s certificate in tailoring during a formal ceremony at the Craftsmen’s Hall in Stavanger, attended by family and friends. The editor of Stavanger Aftenblad, Christian S. Oftedal, delivered the keynote address, and Police Chief Ola Kvalsund presented the certificates. On the same page of the newspaper Stavangeren that covered the ceremony, there were images of Hitler entering Vienna and German troops marching through the city.

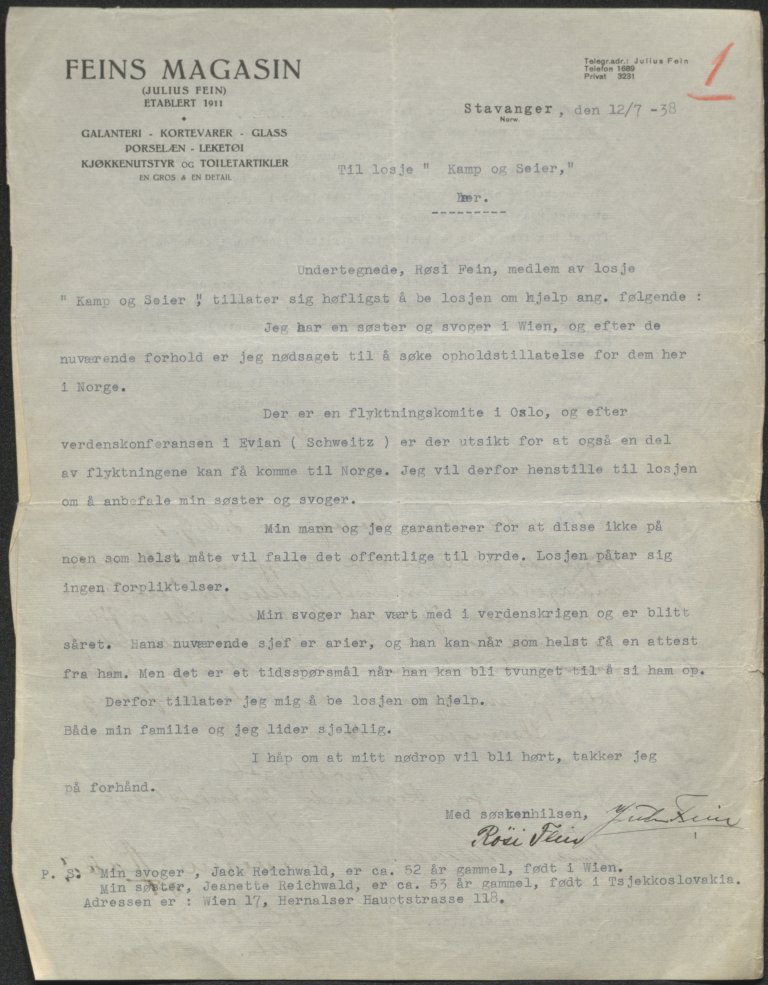

A Cry for Help from Stavanger

As early as May 1938, Julius began the application process to bring his nephew Hans to Norway. After further consideration, the application was approved, and in early July, Hans received a one-year residence permit.

Around the same time, Rösi was actively engaged in humanitarian and civic work. She was a committed member of the lodge Kamp og Seier (Struggle and Victory), part of the International Organisation of Good Templars (I.O.G.T.), a global movement promoting temperance, peace, and social responsibility. The lodge emphasized moral integrity, solidarity, and civic engagement – values that closely aligned with Rösi’s own convictions. Her involvement reflected a deep commitment to both personal and collective efforts for justice and compassion.

That summer, she wrote a heartfelt letter to the lodge, appealing for support in securing residence permits for her sister Jeanette (53) and brother-in-law Jakob (52). In the letter, she explained that Jakob had served in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I and had been wounded. He now faced the risk of losing his job solely because of his Jewish background. Rösi described the letter as a “cry for help” and emphasized the emotional distress felt by both the family and herself. Julius also signed the appeal.

Solidarity in Action

On the reverse side of the letter, “Kamp og Seier” included a statement of support and forwarded it to the Rogaland District Lodge. They emphasized Rösi’s longstanding commitment to the lodge and her reputation as a person with strong humanitarian values. The lodge stated that it “also feels it is our duty to do what we can to help.” The district lodge endorsed the recommendation and and forwarded the letter to the Grand Lodge of I.O.G.T. Norway, which also gave its full support. Through the lodge network, Rösi and Julius’s plea for help was actively championed – an expression of solidarity and compassion. At the same time, it illustrates how the Fein couple called upon their social connections to gather support in a time of crisis.

To the lodge “Kamp og Seier”, dear brethren,

I, Rösi Fein, member of the lodge “Kamp og Seier”, respectfully request the lodge’s assistance regarding the following matter: I have a sister and brother-in-law in Vienna, and due to the current circumstances, I am compelled to apply for residence permits for them here in Norway.

There is a refugee committee in Oslo, and following the international conference in Evian (Switzerland), there is hope that some refugees may be allowed to come to Norway. I therefore appeal to the lodge to recommend my sister and brother-in-law.

My husband and I guarantee that they will in no way become a burden to the public. The lodge assumes no obligations.

My brother-in-law served in the World War and was wounded. His current employer is Aryan, and he can obtain a reference from him at any time. However, it is only a matter of time before he may be forced to dismiss him. That is why I respectfully ask the lodge for help. Both my family and I are suffering emotionally.

In the hope that my cry for help will be heard, I thank you in advance.

With fraternal regards,

Rösi Fein

Julius Fein

P.S. My brother-in-law, Jack Reichwald, is approximately 52 years old, born in Vienna. My sister, Jeanette Reichwald, is approximately 53 years old, born in Czechoslovakia. Their address is: Vienna 17, Hernalser Hauptstrasse 118.

First Attempt: Application for Residence

The application process initiated by Rösi and Julius Fein proved both lengthy and demanding. The first application for residence permits for Jakob and Jeanette Reichwald was submitted on 13 August 1938.

The police in Stavanger were skeptical. In the initial assessment, Police Inspector A. Lahlum wrote:

In view of the consequences, I do not find it possible to recommend that the application for residence permits for Jack and Jeanette Reichwald be granted.

Stavanger Police Department, 23 August 1938

A. Lahlum, Police Inspector

Centralpasskontoret (The Central Passport Office) followed the recommendation from the Stavanger police and rejected the application. One of the decisive arguments was that Julius Fein’s income and assets were deemed insufficient to support his relatives long-term.

Second Attempt: Application for Temporary Residence

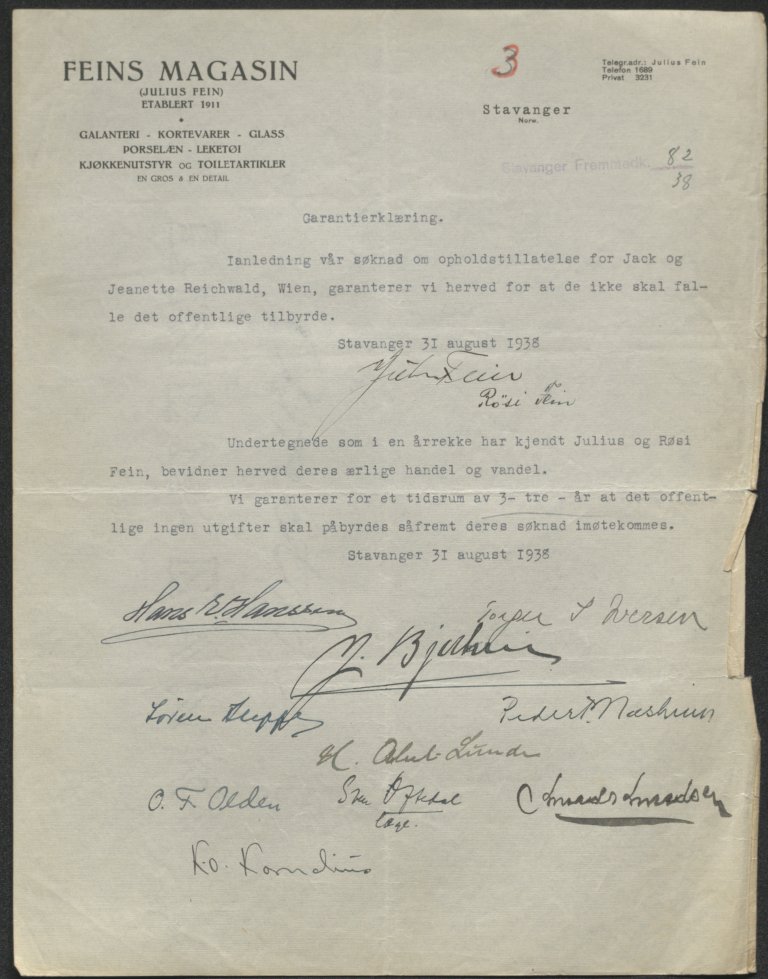

The Fein couple refused to give up. On September 3, 1938, they submitted a new application – this time seeking a two-year temporary residence permit. With help from attorney L. Sirevaag, they included written guarantees from ten local men who pledged their support. These individuals vouched for Rösi and Julius Fein’s good character and committed to covering any expenses for up to three years if the application was approved.

To support their case, the attorney submitted an overview of the guarantors’ financial standing. Several of them were well-off. Together, the ten guarantors held assets exceeding 1.5 million Norwegian kroner (NOK) and reported an combined annual income of nearly 176,000 Norwegian kroner (NOK) – substantial sums by the standards of the time. The documentation was intended to demonstrate that there was strong financial support within the local community, and that Jakob and Jeanette Reichwald would not pose a financial burden to the public.

Still, the second application was denied. Despite the guarantees and backing from respected members of the community, the authorities remained concerned that the Reichwalds might eventually require public financial assistance.

In connection with our application for residence permits for Jack and Jeanette Reichwald of Vienna, we hereby guarantee that they will not become a burden on public welfare.

Stavanger, August 31, 1938

Julius Fein

Rösi Fein

Statement of Support

Having known Julius and Rösi Fein for many years, we hereby attest to their honest conduct and good reputation. We guarantee, for a period of three years, that no public expenses shall be incurred should their application be approved.

Stavanger, August 31, 1938

Hans E. Hanssen, Søren Kleppe, H. Abel-Lunde, O. F. Olden, Torger S. Iversen, J. Bjorheim, Peder P. Næsheim, K. O. Korneliussen, Sven Oftedal, M.D.

A Strict Regulatory Framework in the Background

While the Fein couple worked to bring their relatives to Norway, immigration policies were tightened. Two circulars from Centralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office), sent to police chiefs across the country on September 3 and October 3, 1938, outlined specific procedures for handling German nationals – particularly Jews – at border crossings and in residence applications.

The circular dated September 3, 1938 (Ref. 2655-38) noted that German passports, particularly those issued to Jews, were often marked “valid only for emigration,” with annotations such as “für Ausland, zur Auswanderung.” Although such passports did not formally prevent return to Germany, many feared reprisals upon reentry.

This creates many difficulties for Norwegian authorities, who are, in a way, placed in a forced position when deciding on the applicant’s request for a residence permit.

To avoid this situation, Centralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office) recommended a strict approach:

Under these circumstances, the Central Passport Office considers it most appropriate that German citizens presenting such passports at border control be denied entry and turned away, unless they possess a document showing that they have received permission from Centralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office) to settle in Norway.

The circular dated October 3, 1938 (Ref. 3878-38) further tightened this policy. It pointed out that German citizens – especially Jews – continued to arrive in Norway in large numbers, despite earlier restrictions. Centralpasskontoret (The Central Passport Office) warned of a potential mass emigration and wrote:

This situation creates many difficulties for Norwegian authorities, and the difficulties grow with each passing day.

It was therefore recommended that passport officers, after thoroughly reviewing the passport and interviewing the holder, deny entry to individuals if there was reasonable cause to believe they had left their home country with no intention of returning. Additionally, the circular emphasized:

This approach should not be applied only to German citizens. Due to the antisemitic movement in Italy and the current unrest in Czechoslovakia – which may also lead to mass emigration – the same practice should be applied to foreigners holding Italian and Czech passports.

Against this regulatory backdrop, the Reichwalds’ application was reviewed. Even with extensive guarantees and documentation, their case was evaluated under a policy that, in practice, made it extremely difficult for Jewish refugees to be granted residence – especially on a permanent basis.

Appeal – and a New Assessment

On September 30, the Fein couple submitted an appeal to the Ministry of Justice. They referred to the two previous rejections and argued that the reasoning behind them was insufficient: “The strength of this argument speaks for itself – and says very little.”

Their main objection was that the authorities believed Jakob and Jeanette Reichwald could become a financial burden on the state. The Stavanger police also assumed the couple would remain in Norway for the rest of their lives, even though the application only requested a two-year stay. The Fein couple regarded this as an unfounded assumption. In their communication with the Ministry of Justice, they clarified: “Our intention was to have them relocated to Palestine before the residence permit expired, or send them back to Germany, as the persecution of Jews surely cannot last forever.” They therefore asked the ministry to reconsider the case and approve the application. This prompted both Centralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office) and the Stavanger police to conduct a new review.

However, there was little indication that the police’s assessment had changed. Just three days later, a new statement was issued by the Stavanger Police Department – and the tone remained unchanged. The earlier position continued to influence the outcome, and the financial guarantees were not given decisive weight.

In their renewed statement, the police wrote:

If the parents are also granted residence permits, the Fein couple will have secured residence for four foreigners, who may eventually become a burden on public welfare.

(Stavanger Police Department, October 3, 1938. Inspector Erling Oftedal and Police Attorney Eilert Arff)

To Oslo to Make Their Case

In the fall of 1938, Rösi traveled to Oslo to speak directly with the case officer and to reach out to key political figures. Approximately one month prior to the approval of the residence permit, at the time, Minister of Foreign Affairs Halvdan Koht wrote to Minister of Justice Trygve Lie: “I believe the police in Stavanger are being too distrustful in this case. But take a look at it.”

“No Guarantee of Safety” – But a Glimmer of Hope

In a letter to Centralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office) during the application process, Julius Fein expressed concern about developments in Europe – but also a hope for safety in Norway:

I myself have no guarantee of how long I can retain my rights here in Norway. Jews have felt safe in Austria, Italy, and Czechoslovakia, but we now see what their fate has become. Even Beneš has been forced to leave his position. Therefore, I do not believe even a statesman has a guarantee of holding his position for life, and for that reason I am pessimistic.

At the same time, he conveyed a belief that Norway could still be a peaceful and safe place:

If we are allowed to live in peace here in Norway, it will not be difficult for me financially to support my relatives, and I respectfully ask you to approve my application.

This tension between fear and hope offers insight into how Julius experienced the situation. It reflects both realism and a willingness to take responsibility. He was aware of the dangers, yet still trusted that Norway could be a place of refuge.

A Demanding Application Process

In a letter to Centralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office) dated November 12, 1938, Julius concluded:

But as the matter remains undecided, I respectfully ask you to show goodwill and approve my application, so that my relatives may leave Vienna as soon as possible, as they are in great distress. My wife is completely broken down, as she suffers with her family and we are able to help them. For that reason, I ask for a swift decision. Yours respectfully, Julius Fein.

Personal and Political Commitment

Alongside the formal application process, Rösi and Julius actively engaged in public discourse. In the fall of 1938, Rösi gave a speech at Vennenes Samfunn (the Society of Friends) in Stavanger during a visit from a Czechoslovak trade delegation. She emphasized the importance of mutual understanding between nations and described how, after 21 years in Norway, she had come to feel at home:

Here I have found my second homeland, and I can, with a sincere heart and clear conscience, sing: Yes, we love this country.

She also asked the delegation’s representative to convey a message back home:

We who now live in our new homelands follow, with anxiety and sorrow, the fate of our beloved country, and we pray to God to protect it from the terrible danger that threatens it. 'Truth prevails'.

Julius contributed with historical insight and a strong sense of moral responsibility. In November 1938, he gave a lecture on Jewish history to Madlalaget, placing the events unfolding in Germany in a broader historical context. The talk was met with great interest, and a collection was taken up to support refugee efforts.

A Hard-Won Approval

After a long and demanding process, Jeanette and Jakob were finally granted a residence permit, valid until December 13, 1939. For the Fein couple, this meant that their brother-in-law and sister-in-law could leave behind a life marked by political unrest and economic uncertainty in Vienna and come to Norway. The decision was likely received with deep relief and gratitude. They had long hoped to offer them a safer and more stable life in their home in Stavanger. In their applications, they described the emotional toll of knowing that close family members were living in hardship.

A Welcoming Community and Active Engagement

After Jeanette and Jakob were granted residence in Norway and moved into the home of their hosts at Figgjogata 11 in Stavanger in December 1938, Rösi and Julius continued their active involvement in both business and local associations. They ran Fein’s Magasin – a familiar part of the city for nearly 30 years. The store offered a wide range of goods, with something for every taste and age. Among the items for sale were men’s underwear, shirts, silk stockings, enamel washbasins, scrubbing brushes, shaving soap, handbags, dolls, balls, and toothbrushes.

Alongside their business activities, they were deeply engaged in civic life. In January 1939, Julius gave a lecture on Jewish issues at the city’s temperance society, and later at the Hillevåg Workers’ Association. He also donated a prize to the women’s branch of the Norwegian Seamen’s Union.

Rösi was particularly committed to peace work and international affairs. She was re-elected to the board of the Stavanger Peace Association and gave several lectures on political, historical, and cultural developments in Czechoslovakia – at the workers’ temperance society Frisinn in Stavanger in February 1940, and the following month in Haugesund and Kristiansand.

That Rösi and Julius continued to give lectures and stay engaged in civic life suggests they believed in knowledge and dialogue as means of promoting change. They may have wished to contribute to the community by sharing their experiences and insights. For Jeanette and Jakob, this engagement may have provided a sense of security and stability – and a sense of normalcy in an otherwise turbulent time.

In a democratic society, where freedom of expression is a fundamental right, it may have been especially meaningful to experience an environment where differing opinions were respected and open dialogue was welcomed. For Jeanette and Jakob, being part of a community where one could speak freely and participate in discussions – without fear of consequences – may have offered a sense of safety and belonging. At the same time, there were reminders that antisemitism also existed in Norway. Meanwhile, their sons were beginning to find their place in Norwegian society.

Wilhelm and Hans: Lives in Transition

Wilhelm, the elder son, lived in the city. He had completed his military training in Norway and worked as a tailor for master tailor Ernst Ericson at Østervåg 36. In the autumn of 1939, following Germany’s invasion of Poland, Wilhelm served for two months as part of Norway’s neutrality guard.

Hans, the younger son, also lived in Stavanger. As early as August 1938, he contacted the American consulate in Oslo to explore the possibility of immigrating to the United States. At the end of September, he sent a formal letter inquiring about visa requirements. The consulate replied in October, stating that since Hans had no financial assets, he would need to declare how much money he intended to bring with him upon arrival. This was in line with the consulate’s standard practice for other applicants.

The correspondence continued into the following spring. In May, the consulate wrote: “until you are in a position to show substantial personal Resources it will not be possible to approve Your Application and request a German quota number for Your use.” At the same time, Hans tried to strengthen his application by obtaining an Affidavit of Support from relatives in the U.S., confirming that he would receive financial assistance upon arrival. As part of this effort, his uncle Julius forwarded the documentation to the Central Passport Office in the summer of 1939. The goal was to demonstrate that the family was actively working to help Hans emigrate and that financial support was secured.

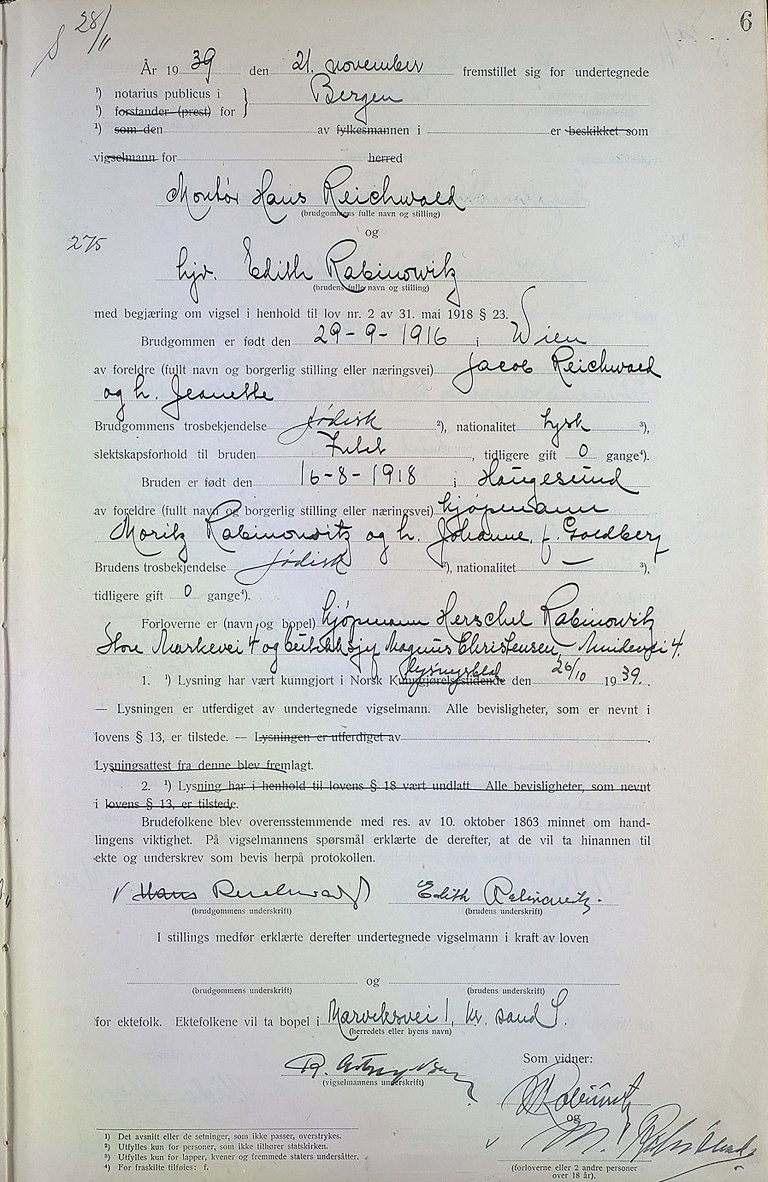

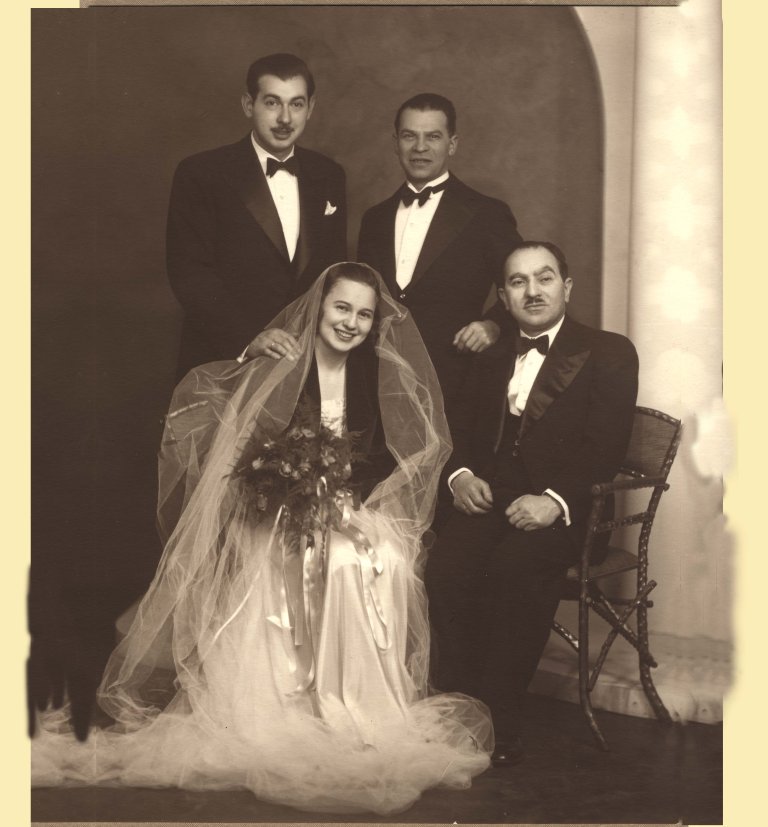

While this process was underway, Hans’s life took a new turn. In the autumn of 1939, he married Edith Rabinowitz at the City Magistrate’s office in Bergen. Just four days after the wedding, Edith’s mother, Johanne, passed awayfollowing surgery at the hospital.

The groom, Hans Reichwald, born September 29, 1916, in Vienna, was the son of Jacob Reichwald and Jeanette Reichwald. His religious affiliation is listed as Jewish, and his nationality as German. He had not been previously married and had no familial relation to the bride.

The bride, Edith Rabinowitz, born August 16, 1918, in Haugesund, was the daughter of merchant Moritz Rabinowitz and Johanne Rabinowitz (née Goldberg). Her religious affiliation is also Jewish, and her nationality Norwegian. She had not been previously married.

The witnesses to the marriage were merchant Herschel Rabinowitz (uncle of the bride), and store manager Magnus Christensen (who served as managing director in the bride’s father's company, Dressmagasinet A/S in Bergen).

The marriage banns were published on October 26, 1939. In accordance with the royal resolution of October 10, 1863, the couple was reminded of the solemnity of the act. Upon being asked by the officiant, both parties declared their intent to marry and signed the official record as confirmation.

Following the ceremony, the couple established their residence at Marviksvei 1 in Kristiansand S.

Shortly after this event, the couple moved to Kristiansand, and the marriage was therefore also recorded in the church register there. In the city, Hans had already begun working in his father-in-law's business, City Dress Magasin A.S., and eventually took over as chairman of the board.

Wilhelm, as an adopted foster son, had been granted residence in Norway, while Hans – like his parents – had to apply for permission to remain. The future was uncertain.

Hans is standing behind Edith. To the left in the background is Edith’s uncle, Herschel Rabinowitz, and seated in the front right is her father, Moritz Rabinowitz.

Photographer: Unknown Haugalandmuseet, MHB-F.003074

Norwegian Authorities’ Treatment of Jewish Refugees

As immigration increased and political unrest spread across Europe, Norwegian authorities became increasingly focused on regulating and controlling the arrival of refugees – particularly Jews. On May 15, 1939, the Ministry of Justice issued a circular to Centralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office) with guidelines for how Jewish refugees were to be questioned.

The circular was prompted by criticism that authorities had asked about racial categorization – specifically, whether a person should be considered Jewish or Aryan. The Ministry emphasized that such questions did not reflect the Norwegian government’s stance on different ethnic groups, but were tied to assessing the legal basis for residence and applicable regulations.

It was clarified that it could be relevant to ask whether a person was considered Jewish under the laws of their home country, as this could affect whether they qualified as a refugee. At the same time, the circular stressed:

The questioning should always be conducted in such a way that the individual understands the aim is to clarify their refugee status, and that Norwegian law does not recognize any distinction between people based on race. The term ‘Aryan’ should always be avoided.

The circular was signed by Minister of Justice Trygve Lie and Director General Platou. It was forwarded to the Stavanger Police Department, where five employees marked it as “Seen” and added their initials.

Living in Uncertainty

Questions surrounding residence permits shaped the lives of Jeanette and Jakob during their time in Norway. They were required to renew their permits regularly, and uncertainty about their future remained a constant concern. Julius was obligated to demonstrate that he was actively seeking to relocate his brother-in-law and sister-in-law to another country, though this proved difficult. In a letter to the Stavanger Police Department dated August 2, 1939, he wrote:

Regarding Jack Reichwald and his wife, it is currently hopeless to get them out of here. They cannot enter America because Mrs. Reichwald is ill and undergoing medical treatment.

Julius enclosed medical documentation confirming this. He also emphasized that Reichwald had assets amounting to 10,000 kroner, paid taxes to the municipality of Stavanger, and held a six-year residency guarantee. He concluded the letter with the expectation that this should be sufficient for the couple to justify continued residence in Norway for the foreseeable future.

Despite signs of antisemitism in society – including during the May 17 celebrations in the spring of 1939 – the efforts to secure continued residence persisted. In December of that year, Julius applied for a one-year extension of the residence permit for his brother-in-law and sister-in-law. The application was immediately recommended by the Stavanger Police Department and approved by Sentralpasskontoret (the Central Passport Office) until mid-December 1940.

May 17, 1939 – Antisemitic Incident in Stavanger

In the spring of 1939, Herman Becker was a Norwegian high school graduate (“russ”) in Stavanger. He was the son of one of the city’s few Jewish families – and the only Jewish student among those specializing in business (“blåruss”). During the May 17th parade, a placard was displayed with the message: “War will come when trade relations become unbearable. God save us from the merchants,” accompanied by a drawing with clear antisemitic features. A fight broke out between students and business-track graduates, and the placard was torn down.

The newspaper 1ste Mai covered the incident and issued a strong condemnation of racial hatred, calling it “unworthy of enlightened youth.” In the days that followed, several opinion pieces continued the discussion.

The Becker, Fein, and Reichwald families knew each other, and it is likely that the incident was discussed among them. The episode showed that antisemitism was not just a distant European phenomenon - it could also surface within Norwegian youth culture.

The Outbreak of War

When war came to Norway on April 9, 1940, Jeanette and Jakob had been living in Stavanger for just under a year and a half. While we have no direct sources describing how they experienced that day, the watch log from the Stavanger Police Department offers a glimpse of some of the events that unfolded in the city and its surrounding areas.

At 1:30 PM, two German officers arrived at the police station. They conferred with the chief of police. Shortly thereafter, the German flag was raised on the station’s flagpole. B. A. Stangeland The German officers demanded that all shops and cafés close at 6:00 PM.

Already shortly after midnight, the police began receiving reports of unusual activity: a German ship had anchored near Tjuholmen, and the destroyer Ægir was mobilized to investigate. The chief of police ordered the watch to be ready for “anything.” Early that morning, a call came in from Sola Airfield – full alert for the bomber wing – aircraft were taking off. Not long after, Ægir opened fire in the harbor, just a couple of kilometers away from Figgjogata 11 in the Storhaug district. At 08:12, the chief of police personally activated the air raid siren – a clear signal that something serious was unfolding. Later that same day, the German flag was raised over the police station. There was no longer any doubt: German troops had occupied the city.

We don’t know exactly what Jeanette and Jakob witnessed that day. But it’s hard to imagine they didn’t hear the air raid siren echoing across the city on the morning of April 9, 1940. The gunfire from the harbor, when Ægir opened fire, might have startled them awake – or perhaps they slept through it. Maybe it was in that moment they realized – or feared – that the war they had once fled was now catching up with them.

A Home in Harm’s Way

Two days later, on the evening of April 11, Stavanger’s city center was struck by a British bomber that was shot down and crashed in the Storhaug district – just about 500 meters from Figgjogata 11, the home of Jeanette and Jakob for the past fifteen months. Everyone on board the aircraft, along with three civilians, lost their lives.

In the weeks following the incident, daily life became increasingly unsettled as new regulations were introduced. One such measure required Jews to hand over their radios, and Julius complied on May 21. This meant the loss of a vital source of both news and entertainment.

Just a few weeks later, in late June, Julius was arrested in Stavanger and transferred to pretrial detention in Kristiansand. The reason for his arrest was reportedly a “German order.” In a police statement, Julius explained that he was treated as a suspicious individual because of his name and background. He was imprisoned for two weeks before being released. The experience left him frightened and likely made a deep impression on his immediate family.

Taken together, these events show how their home was situated in a danger zone – where access to essential information was restricted, the threat of arbitrary detention was real, and the risk to life and health was ever-present.

A New Place to Stay in Troubled Times

Hans’s nephew, who lived in Kristiansand with his wife Edith, left the city at the end of May 1940 after their apartment was sealed. The couple moved to Skånevik in Sunnhordaland, where they settled in what they considered to be safer surroundings. Edith’s father, Moritz Rabinowitz, had already left his hometown of Haugesund in April and sought refuge in Vindafjord, as he was wanted by the Germans.

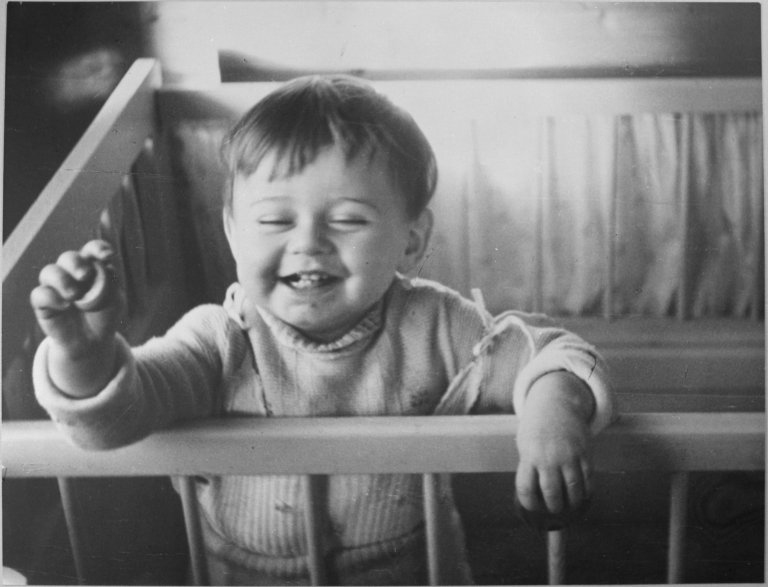

A Glimmer of Hope Amid the Turmoil

Later that same year, in November, Hans and Edith welcomed their son Harry. For Moritz, Jakob, and Jeanette, this meant becoming grandparents for the first time. We don’t know what they thought or felt about this, but it’s reasonable to assume it was a bright spot in an otherwise difficult time. Less than two weeks later, Moritz was arrested and imprisoned in Haugesund Jail. The reason given was that he had engaged in “illegal propaganda.” They never saw him again – though they didn’t know that at the time. Hans eventually completed a business education in Bergen and went on to run a mechanical workshop in Skånevik.

Seeking Refuge in the Countryside

In October 1940, just a few months after Hans and Edith had begun a new life in Sunnhordaland, Jakob and Jeanette relocated to the mountain farm Brådland in Frafjord, which Jakob’s brother-in-law Julius had rented. According to the local sheriff's register of residents moving in and out, they had been granted an extension of their residence permit in the Rogaland police district until May 31, 1941. The move may have been driven by a desire for safety in an increasingly unstable and unpredictable time.

While Jakob and Jeanette were living at Brådland, Moritz Rabinowitz was transferred from Haugesund Prison to Oslo. There, he was first held at Møllergata 19 and later at Grini, before becoming one of the first Norwegian Jews to be deported to the German concentration camp Sachsenhausen. He died there in February 1942 – one of the earliest Norwegian Jews to perish in a Nazi camp.

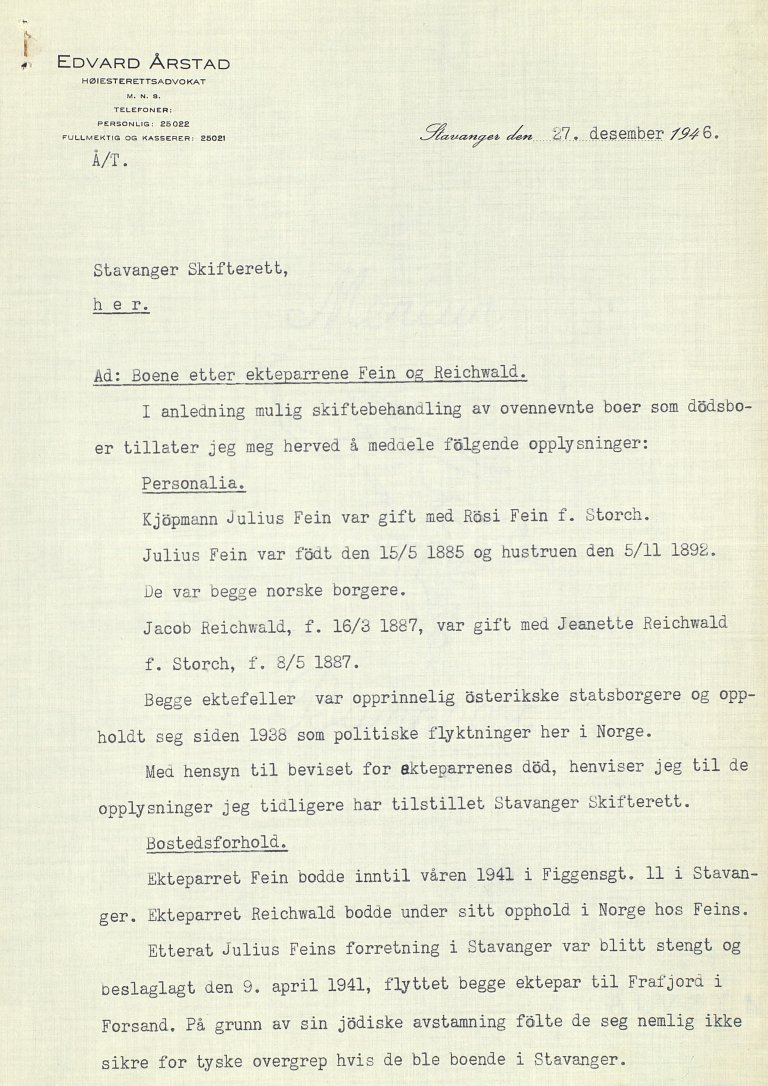

Loss of Security and Livelihood

Exactly one year after the German invasion of Norway, on Wednesday, April 9, 1941, Julius was arrested by the German security police, and his business, Feins Magasin, was shut down. The reason given was that he had allegedly engaged in anti-German activity. In a letter from Supreme Court Attorney Edvard Årstad to the Stavanger probate court (Stavanger skifterett), dated December 27, 1946, it states:

After Julius Fein’s business in Stavanger was closed and confiscated on April 9, 1941, both couples moved to Frafjord in Forsand. Because of their Jewish background, they did not feel safe from German persecution if they remained in Stavanger. […] The business was closed and confiscated on April 9, 1941 by the Sipo (short for Sicherheitspolizei, the German security police), which handled the liquidation of inventory and furnishings. Before the liquidation took place, in the fall of 1941, a significant portion of the inventory had been stolen from the warehouse by the Sipo. The loss is estimated at NOK 40,000. […]

After losing their livelihood, Julius and Rösi also chose to leave the city in the summer of 1941. However, they never officially registered their move with the population registry and kept a room at Figgjogata 11 in Storhaug. Both the older and younger generations relocated from the city to the countryside, and they continued to visit one another.

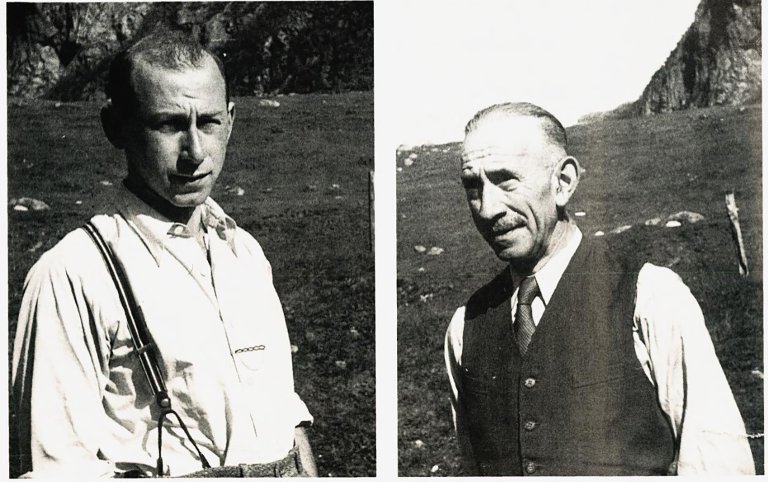

The photo is reproduced from Gudtorm Mikkelson’s book: Gjesdal. Indre del. Gards- og Ættesoge Frafjorddalen og Østabødalen, vol. 1 (1994).

Both images are reproduced from Gudtorm Mikkelson’s book: Gjesdal. Indre del. Gards- og Ættesoge Frafjorddalen og Østabødalen, vol. 1 (1994).

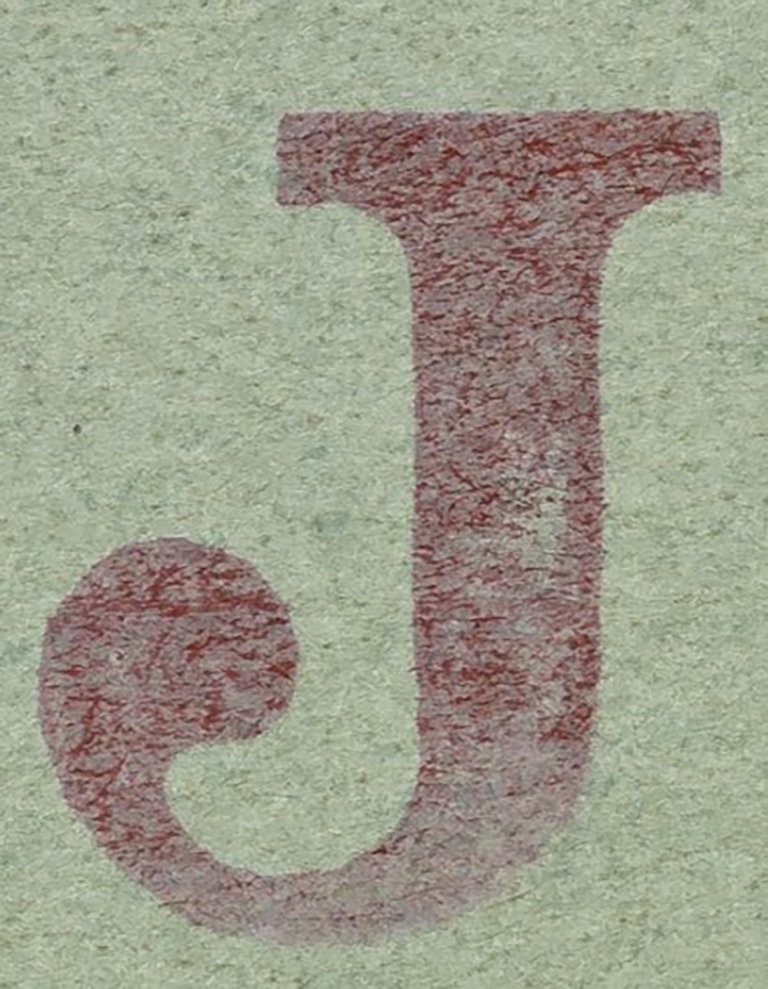

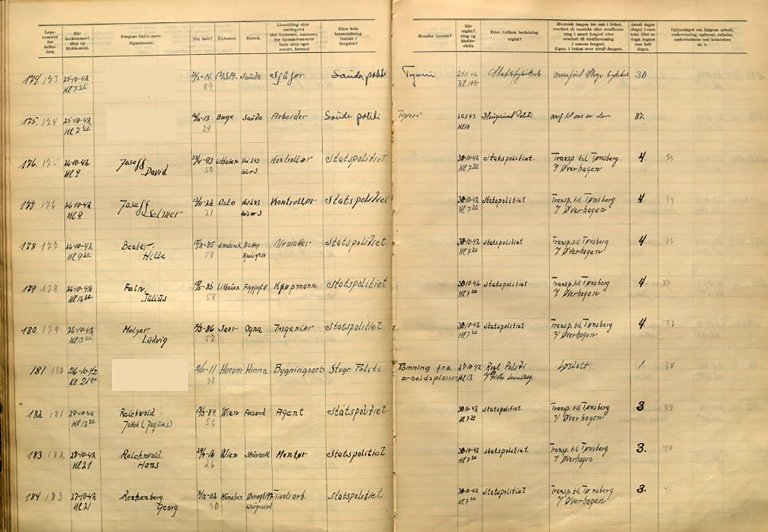

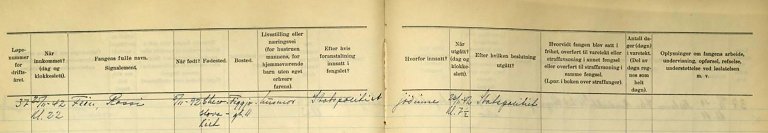

Control Measures and Registration

On January 20, 1942, it was decided that all Jews in Norway were to have a red “J” stamped on their identification cards. Initiated by the German security police and carried out by Norwegian authorities, this measure marked a clear shift in the treatment of Jews.

Following the stamping of identification cards, questionnaires were distributed in the spring of 1942 to all Jews in Norway aged 15 and older. These forms were to be completed in three copies and submitted to the police, the statistical office of Nasjonal Samling (the Norwegian Nazi party led by Vidkun Quisling), and the Ministry of Justice. The questionnaires requested detailed personal information and were part of a systematic registration effort that laid the foundation for the subsequent arrests and deportations.

In March 1942, Jeanette and Jakob completed their questionnaires in Frafjord. Jeanette stated that she was an Austrian citizen, married to Jack, and the mother of Hans. She did not mention Wilhelm, as he had been adopted by other family members. She reported having completed primary and middle school, identified as a member of the Mosaic faith community, and listed her occupation as private housewife – indicating that she worked within her own household and was not employed by others.

Jack provided the same citizenship and religious affiliation. He described himself as a war invalid with a stab wound to his left hip, noted that he had previously worked as an agent, and that he had a business school education. Wilhelm was not mentioned in his form either.

Both declared that they had no assets, were not members of any organizations, and had never been convicted of a crime.

Hans completed his questionnaire a week and a half before his parents, and Wilhelm followed a few days later. Hans’s responses show that he was living in Skånevik, married to Edith, and had a 15-month-old son named Harry. He had trained as a window decorator and held German citizenship. In August 1938 he arrived in Norway and, at the time of completing the questionnaire in 1942, was working as a general repair technician, including bicycle repairs.

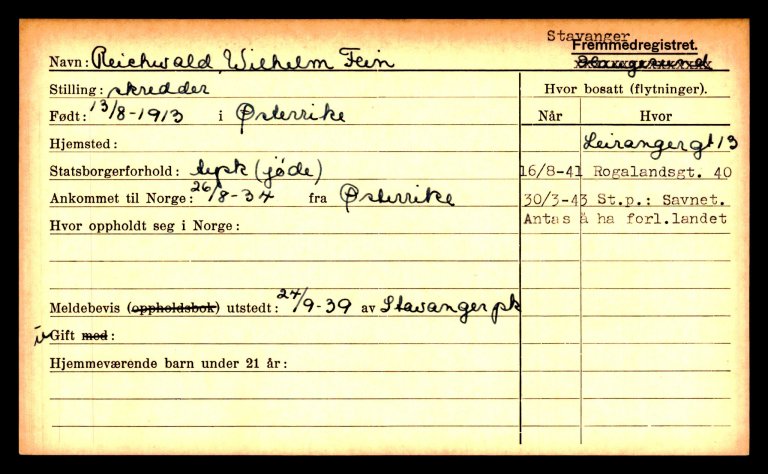

Wilhelm stated that he was unmarried, trained as a tailor, and had completed basic military training in Norway. He came to the country in 1934, was adopted by his aunt and uncle, and considered himself stateless. At the time of completing the questionnaire, he was working as a tailor and lived at Rogalandsgata 40 in Stavanger. Neither Wilhelm nor Hans were members of any clubs or organizations.

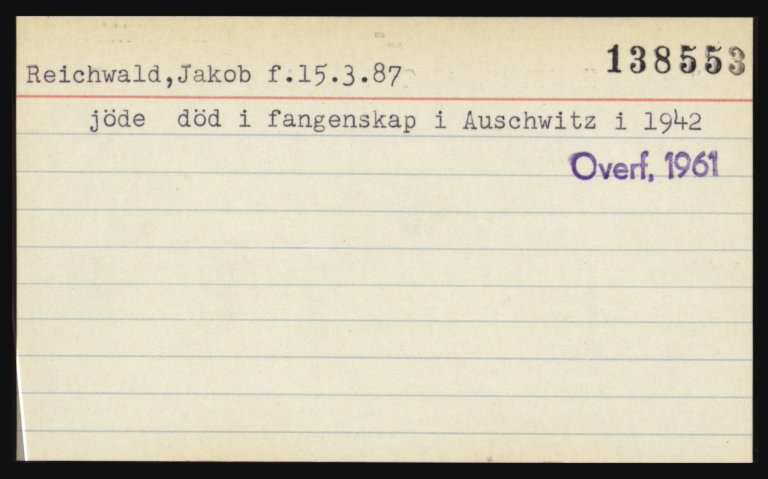

Arrest and Deportation of Jewish Men

On October 26, 1942, the Law on the Confiscation of Property Belonging to Jews (Lov om inndragning av formue som tilhører jøder) was published in Norwegian newspapers. The law applied to Jews with Norwegian citizenship as well as stateless Jews, including their spouses and children. Section 1 stated: “Assets of any kind belonging to a Jew [...] shall be confiscated for the benefit of the state treasury.” Attempts to conceal property could be punished with up to six years in prison. The law took effect immediately and could not be challenged in court.

On the same day the law was enacted, all Jewish men over the age of 15 were arrested. When police arrived at the home of Julius Fein at Figgjogata 11 at 6:00 a.m., he was not at home. According to the report by Officer Kaare Grette, it was Rösi they spoke with before leaving the premises about an hour later. She explained that her husband was visiting Oltedal, where he was apprehended later that day and taken to Stavanger District Prison, Section C, at 12:30 p.m. His brother-in-law Jakob and nephew Hans arrived one day later. No explanation was given for the arrest.

Two days later, Abraham Ramson was brought in. All of them were transported to Tønsberg early in the morning on October 30, under the supervision of Øverhagen.

On October 28, Jakob Reichwald was interrogated by Officer Egil Digerås. During the interrogation, he stated that he was a former Austrian citizen, residing in Vienna. There, he had worked as a sales agent for a sausage factory, but lost his job in 1938 when a law prohibited Jews from working as agents. That same year, he traveled to Norway, arriving on December 13, and settled with his brother-in-law, Julius Fein. His stay was conditional on not taking up employment.

While in Norway, he received financial support from a brother in Sweden – amounting to approximately NOK 3,000. A form attached to the interrogation report notes that his wife, Jeanette, was required to report daily to the sheriff in Forsand.

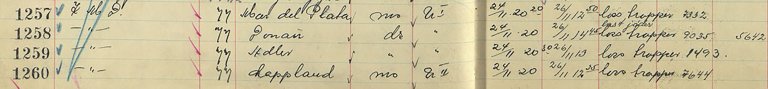

On October 30, Jakob, Hans, and Julius were taken to Berg internment camp (Berg interneringsleir) outside Tønsberg, along with other Jewish men arrested in Rogaland. After a brief stay, they were deported on November 26 aboard the German steamship Donau, used by the Nazi regime to transport more than 500 Jews from Norway.

Photo: Georg W. Fossum’s original negatives from 1942, available through the National Library of Norway.

Edith Reichwald – Request to Relocate to Family in Stavanger

Two days after her husband was arrested, Edith applied to move with her nearly two-year-old son, Harry, to Stavanger, where she intended to live with her mother-in-law at Figgjogata 11. She applied for relocation because she no longer had any family or close contacts in Skånevik. The local sheriff (lensmannen i Skånevik) recommended the request and forwarded it to the State Police in Bergen (Statspolitiet i Bergen), who approved it in early November – on the condition that she report daily to the police in Stavanger.

In her application, Edith wrote:

I, Mrs. Edith Reichwald, residing in Skånevik, and required to report daily to the police due to my Jewish background, hereby apply to travel to Stavanger to live with my mother-in-law, Mrs. Janett Reichwald, Figensgt. 11.

My husband, Hans Reichwald, was arrested on the 26th of this month, and I am now alone here in Skånevik with my young son, Harry, who is two years old.

I have no family or relatives here in Skånevik.

Skånevik, October 28, 1942

Edith Reichwald

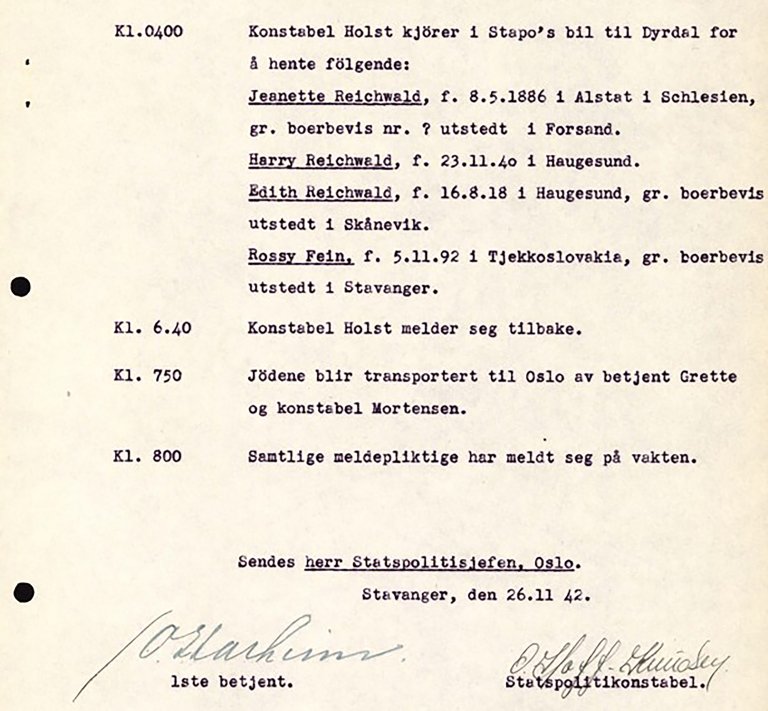

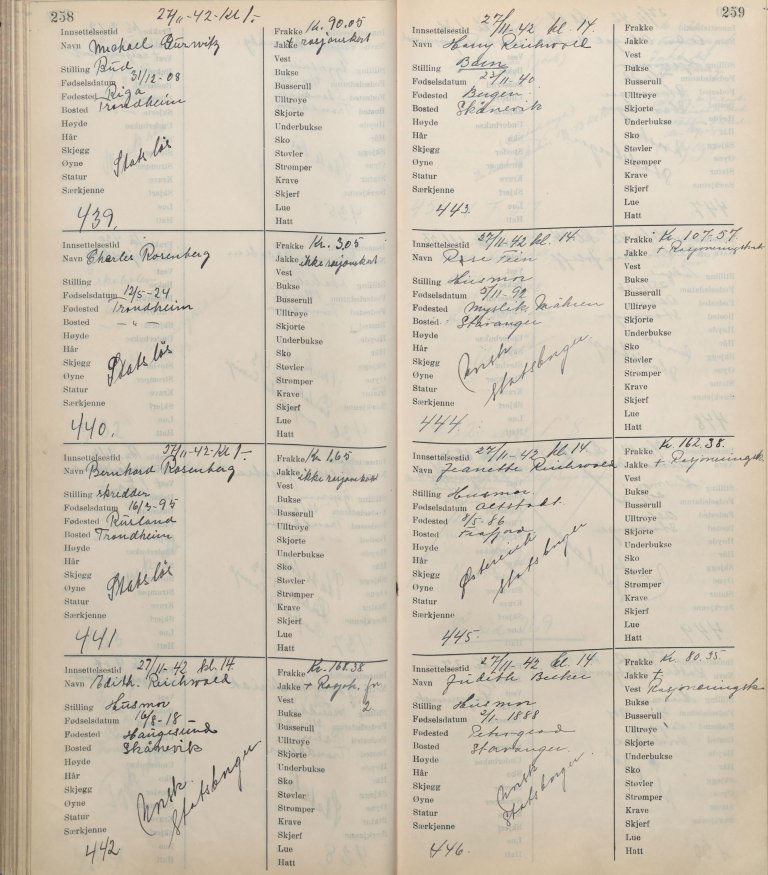

Arrest of Women and Children

Edith’s stay in Stavanger – or more precisely, in Frafjord, where she had actually relocated – was brief. One month after the arrest of the male family members, the women and children were next. During the night between November 25 and 26, 1942 – just two days after Harry turned two – he, his mother Edith (24), grandmother Jeanette (56), and her sister Rösi (50) were arrested along with five other Jewish women: Selma Nilsen (22), Hildur Sara Joseff (26), Ida Ottesen (35), Ada Abigael Becker (20), and Judith Becker (54).

The police report from the Stavanger Division of the State Police (Statspolitiet) shows that all were taken into custody following an order issued by Police Inspector Ekerholt.The arrests were part of the coordinated deportation of Jews from Norway on November 26, 1942.

Brief Detention in Stavanger

Early in the morning, Constable Holst drove to Dirdal to collect the three women and the young boy. During the night, they had been transported there by Sheriff Espedal (lensmann Espedal). Shortly after arriving in Stavanger, all the arrested Jews were transferred to Oslo by Officer Grette and Constable Mortensen.

4:00 a.m. – Constable Holst (konstabel Holst) drives the State Police vehicle (Stapo’s bil) to Dyrdal to collect the following individuals:

Jeanette Reichwald, born May 8, 1886, in Altstat, Schlesien. Border resident certificate (grenseboerbevis) issued in Forsand.

Harry Reichwald, born November 23, 1940, in Haugesund.

Edith Reichwald, born August 16, 1918, in Haugesund. Border resident certificate issued in Skånevik.

Rossy Fein, born November 5, 1892, in Czechoslovakia. Border resident certificate issued in Stavanger.

6:40 a.m. – Constable Holst reports back.

7:50 a.m. – The Jews are transported to Oslo by Officer Grette and Constable Mortensen.

8:00 a.m. – All individuals required to report for duty have checked in.

To be forwarded to the Chief of the State Police (Statspolitisjefen), Oslo

Stavanger, November 26, 1942

Overnight Stay at Kristiansand District Prison

The journey from Stavanger to Oslo was long and demanding. Before the Sørlandet Railway (Sørlandsbanen) between Kristiansand and Sira opened in December 1943, there was no direct train connection between the two cities. Travelers first had to take a train to Flekkefjord – a trip of about five hours – followed by a bus or car ride to Kristiansand, which took another four to five hours.

In the detention register (varetektsprotokollen), the stated reason for imprisonment is: “Transport from Stav to Oslo.” [Note: “Stav” likely refers to Stavanger.]

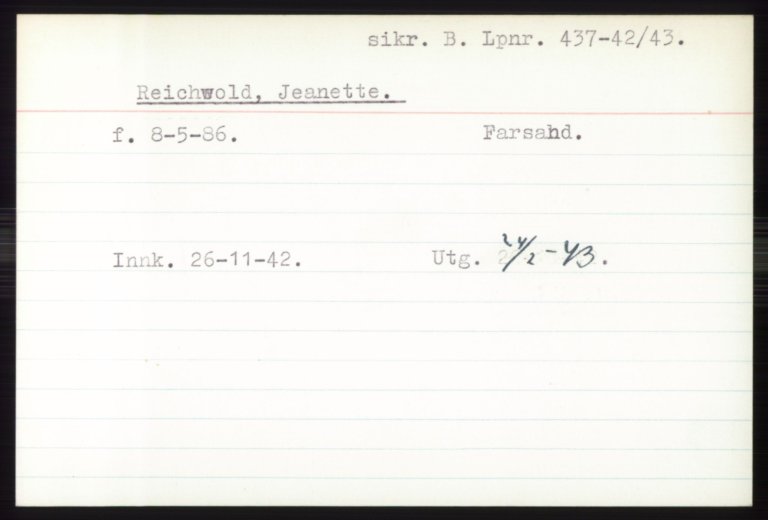

Detention in Oslo and Deportation

The intake register (mottakelsesprotokollen) at Bretveit Prison (Bretveit fengsel) shows that Jeanette, her sister Rösi, her daughter-in-law Edith, and her grandson Harry arrived on November 27, 1942, at 2:00 p.m. All three women carried cash and ration cards, which they were required to hand over.

After spending several months at Bredtveit Prison, they were forcibly deported from Norway. According to prisoner records and the register of so-called "security detainees", they left the prison on February 24, 1943. The ship Gotenland, which transported them, departed from Filipstadkaia in Oslo in the early morning hours the following day. The dock journal records the departure time as 5:10 AM.

Their next destination was the German concentration camp Auschwitz.

While Edith was being transported to Auschwitz, her father Moritz died in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. She most likely never learned of his death, as she is believed to have been taken directly to the gas chamber upon arrival – six days after her father’s passing.

None of them – Jeanette, Edith, Harry, Rösi, Jakob, Hans, or Julius – ever returned.

Stavanger, December 27, 1946

Stavanger Probate Court (Stavanger Skifterett)

Re: The estates of the Fein and Reichwald couples

In connection with the possible probate proceedings for the above-mentioned estates as estates of the deceased, I hereby submit the following information:

Biographical Details

Merchant Julius Fein was married to Rösi Fein (née Storch). Julius Fein was born on May 15, 1885, and his wife on November 5, 1892. Both were Norwegian citizens. Jakob Reichwald, born March 16, 1887, was married to Jeanette Reichwald (née Storch), born May 8, 1887. Both couples were originally Austrian nationals and had lived in Norway as political refugees since 1938. As for proof of their deaths, I refer to the information previously submitted to the Stavanger Probate Court (Stavanger Skifterett).

Residence History

The Fein couple lived at Figgensgt. 11 in Stavanger until the spring of 1941. During their time in Norway, the Reichwalds resided with the Feins. After Julius Fein’s business in Stavanger was closed and confiscated on April 9, 1941, both couples moved to Frafjord in Forsand. Due to their Jewish heritage, they no longer felt safe remaining in Stavanger, fearing persecution by German authorities.

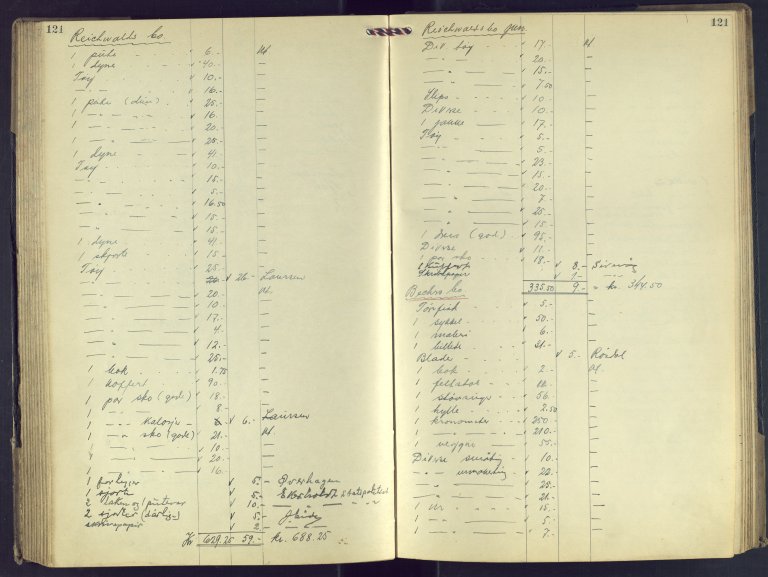

Items Under the Hammer

Shortly after Jeanette and Jakob were deported from the country in which they had sought refuge, their belongings were sold at two public auctions. On March 19 and April 29, 1943, personal effects once belonging to them were auctioned off in Stavanger.

Each item is listed with its price and payment method.

Items marked with “kt” (short for kontant, meaning cash) were paid for immediately. Items without this designation were purchased on credit.

1 pillow – NOK 6 (cash)

1 duvet – NOK 40 (cash)

Fabric – NOK 10 (cash)

Fabric – NOK 16 (cash)

1 down pillow – NOK 25 (cash)

1 down pillow – NOK 16 (cash)

1 down pillow – NOK 20 (cash)

1 down pillow – NOK 25 (cash)

1 duvet – NOK 41 (cash)

Fabric – NOK 10 (cash)

[...]

Some items were purchased on credit by named individuals or institutions:

1 book publisher – NOK 5 – Øverhagen

1 shirt – NOK 5 – Ekerholdt, State Police

2 sheets and 1 pillowcase – NOK 10 – Ekerholdt, State Police

[...]

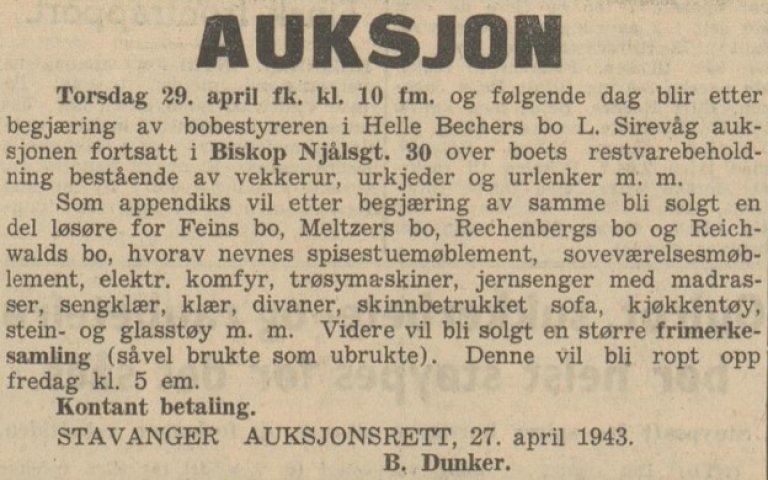

Just over a month later, at the very end of April, the final items belonging to the Reichwald family and other Jewish families in Stavanger were auctioned off. Among the items were: an armchair, a waffle iron, a suitcase, a coffee pot, assorted preserves, and various other household goods. The most valuable item was a stamp collection, which sold for 1,800 NOK.

Auction

Thursday, April 29, at 10 a.m., and continuing the following day, by request of the estate administrator for the Helle Becker estate, L. Sirevåg.

The auction will take place at Biskop Njåls gate 30 and will include the remaining inventory of the estate, consisting of alarm clocks, watch chains, and other timepiece accessories.

As an appendix, and by request of the same administrator, various household items from the estates of Fein, Meltzeer, Rechenberg, and Reichwald will also be sold. These include: Dining room furniture, Bedroom furniture, Electric stove, Sewing machines, Iron beds with mattresses, Bedding, Divans, Leather-upholstered sofa, Kitchenware

Stoneware and glassware, And more.

In addition, a large stamp collection – containing both used and unused stamps – will be auctioned.

This collection will be called at 5 p.m. on Friday.

Cash payment only.

Stavanger Probate Court, April 27, 1943

B. Dunker

Police officers were among the buyers at both auctions – on March 19 and April 29. Some had even taken part in the arrests. State Police Officer Eeg Hansen bought an armchair and a kitchen scale. Chief Officer Starheim purchased saucepans, while Øverhagen acquired a small floor rug. The State Police secured a small lamp, and Chief Superintendent Ekerholt bought shirts, bed sheets, and pillowcases.

Recovered Traces

After the war, efforts were made to return some of the items. The stamp collection was partially recovered after the buyers were identified. The armchair, purchased by Eeg Hansen, was also returned.

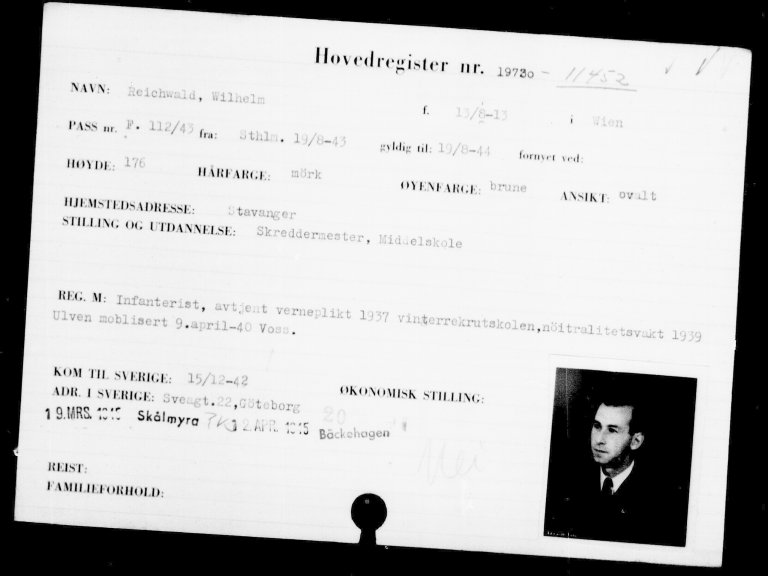

The Only One in the Family Who Survived

The eldest son, Wilhelm Reichwald Fein, was the only member of his family to survive the war years in Norway. Adopted by his aunt and uncle, Wilhelm was living in Oslo in the autumn of 1942, continuing his training as a tailor under a Jewish master craftsman. As the situation grew increasingly dangerous, he managed to flee to Sweden. In March 1943, he was listed as missing in the Central Passport Office’s registry (Centralpasskontoret), with the note: “Presumed to have left the country”.

Name: Reichwald, Wilhelm, born August 13, 1913 in Vienna

Passport No.: F.112/43 issued in Stockholm on August 19, 1943, valid until August 19, 1944

Height: 176 cm

Hair color: Dark

Eye color: Brown

Facial features: Oval face

Home address: Stavanger

Occupation and education: Master tailor; secondary school education

Military service record: Infantryman. Completed mandatory military service in 1937 at a winter recruit training camp. Served in Norway’s neutrality guard in 1939. Mobilized at the Ulven camp on April 9, 1940, and later stationed in Voss.

Arrived in Sweden: December 15, 1942

Address in Sweden: Sveagatan 22, Gothenburg

Archives as Memory and Resistance

Jeanette and Jakob Reichwald came to Norway in search of safety and family reunification. But their stay did not turn out to be the refuge they had hoped for. The archives and historical sources that document their lives and fate remain as traces of people who were denied the chance to live on – and whom we have a responsibility to remember.

The story of Jeanette and Jakob Reichwald, and the family who tried to save them, is documented across various archival records and other sources. These records do not offer a complete picture, but fragments that allow us to understand, remember, and learn. The narratives that emerge from the archival material remind us that migration is not just about numbers and statistics – it is about people, relationships, and hope.

The exhibition

This digital exhibition was created by Ine Fintland (Senior Archivist) and Synnøve Østebø (Archivist).

Through this exhibition, we aim to shed light on the traces left behind by the Reichwald family, and to foster reflection on the past, present, and future.

We are grateful for the valuable support and assistance provided by Madli Hjermann (Photo Archivist and Conservator, Haugaland Museum), as well as several colleagues at the National Archives of Norway: Espen Andersen (Senior Advisor), Atle Brandsar (Senior Advisor), Kristian Hunskår (Senior Advisor), Eli Mosvoll-Jakobsen (Advisor), Hanne Karin Sandvik (Senior Advisor), and Eivind Skarung (Senior Advisor).

This article was originally written in Norwegian and translated into English using Copilot, based on the prompt: “Translate idiomatically for an American audience. The article will be published on the website of the National Archives of Norway. Use terminology appropriate for a U.S. readership, and ensure the language is clear and concise.” The final version was reviewed and edited by Ine Fintland and Janet B. Martin (Senior Advisor) for clarity and accuracy.

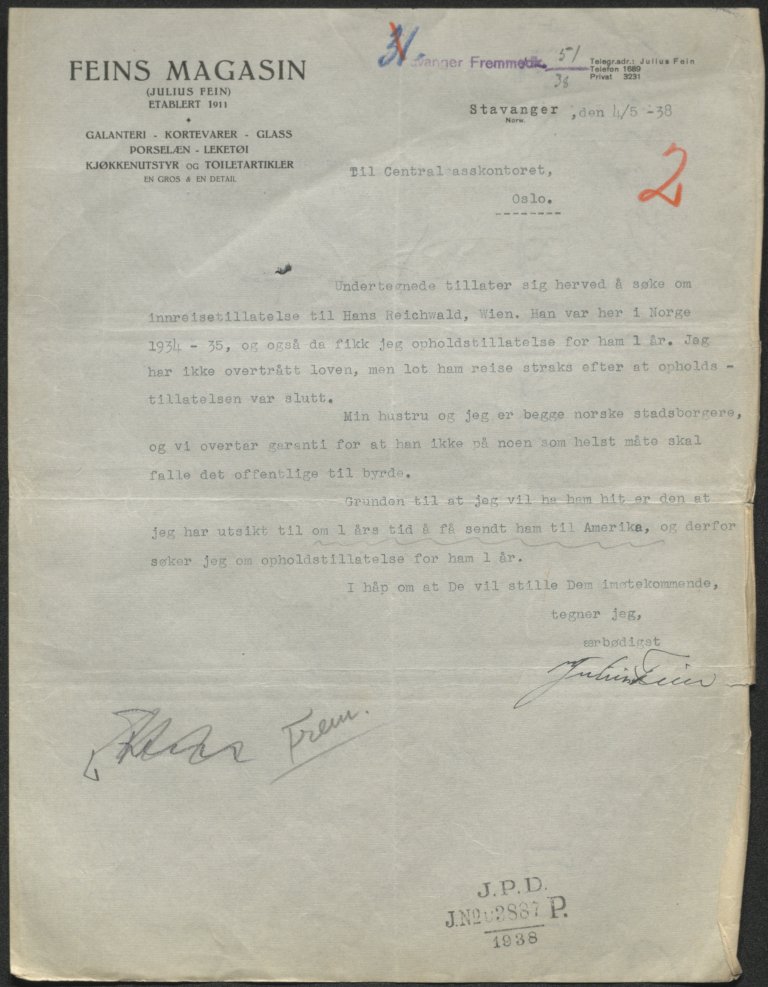

A Year in Safety: The Residence Application for Hans

In early May 1938, Julius Fein applied for a residence permit for his nephew, Hans Reichwald. He explained that Hans had previously spent a year in Norway, and that he and his wife—both Norwegian citizens—guaranteed that Hans would not be a public burden. The aim was to grant him temporary residence in Norway while awaiting the opportunity to relocate him to America within a year.

The application was forwarded to the Chief of Police in Stavanger for review just days after it was received. This was also why Rösi and Julius Fein appeared for an interview at the station. A police report dated May 28, 1938, authored by Deputy Officer Eilert Arff, records the details of that meeting.

The Fein couple explained that Hans was 21 years old, the son of Rösi’s sister, and of Jewish background. They emphasized that he had previously held a one-year residence permit in Norway (1934–1935). He had begun military service when Austria was annexed by Germany in March 1938, but was discharged because he was Jewish. Since then, he had been unemployed, and his father’s income was so low that there was “no possibility of existence or future for him in Austria at present.”

Rösi and Julius stated that they were working to help Hans emigrate to the United States with support from relatives, but were applying for a one-year stay in Norway while the application process was underway. They guaranteed that Hans would not seek employment and would therefore not compete with Norwegian workers for jobs. They also assured the authorities that he “would in no way become a burden on public welfare.”

According to the forwarding document (document 1), on June 11, 1938, the Stavanger Police Department declined to recommend the application, stating: “One may assume that this application is part of Reichwald’s efforts to obtain permanent residence in Norway.” This was also the conclusion reached by the Central Passport Office (Centralpasskontoret) in its decision three days later. Hans Reichwald was initially denied a residence permit.

Julius Fein was formally notified of the rejection on June 17, 1938. About a week later, he contacted the Ministry of Justice and requested that the decision be reconsidered. Roughly two weeks after that, the Ministry of Justice and Police – then under the leadership of Trygve Lie – sent a letter to the Central Passport Office urging them to reverse their earlier decision. A new ruling granting Hans a one-year residence permit was issued the very next day.

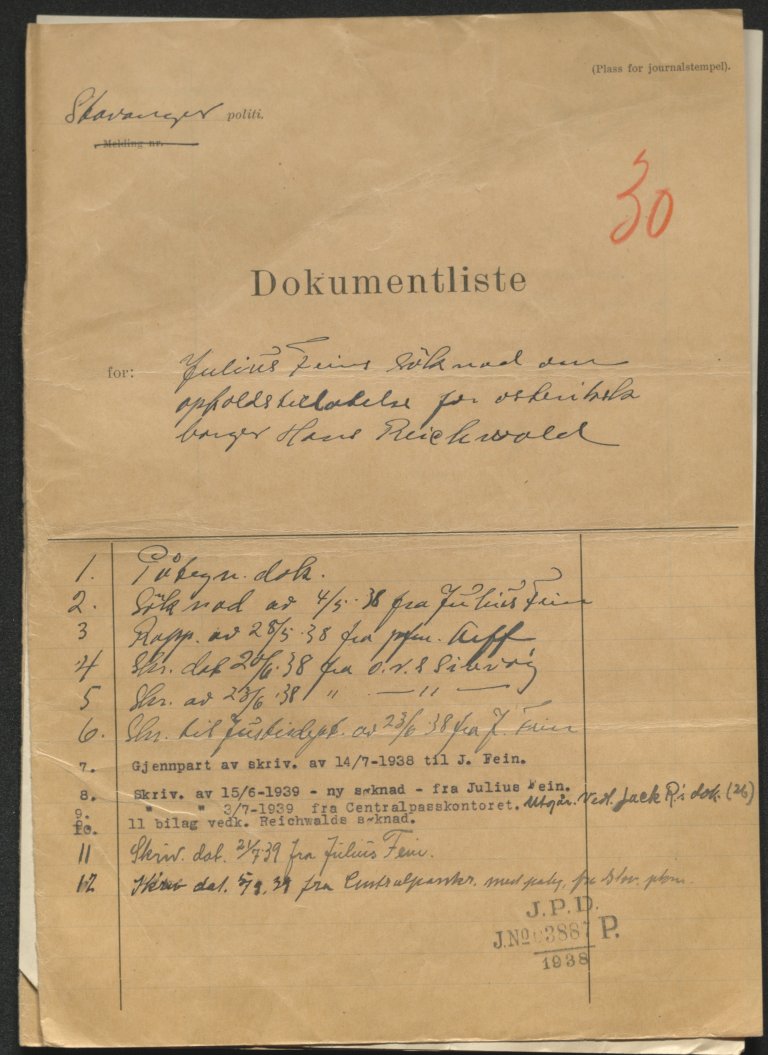

1. Endorsement document

2. Application dated May 4, 1938, from Julius Fein

3. Report dated May 28, 1938, by Deputy Officer Arff

4. Letter dated June 20, 1938, from Magistrate Sirevåg

5. Letter dated June 23, 1938, from Magistrate Sirevåg

6. Letter to the Ministry of Justice dated June 23, 1938, from Julius Fein

7. Copy of letter dated July 14, 1938, to Julius Fein

8. Letter dated June 15, 1939 – new application – from Julius Fein

9. Letter dated July 3, 1939, from the Central Passport Office, excluded due to Jack Reichwald’s document (no. 26)

10. Eleven attachments related to Reichwald’s application

11. Letter dated July 21, 1939, from Julius Fein

12. Letter dated August 5, 1939, from the Central Passport Office with endorsement from the Stavanger Police Department

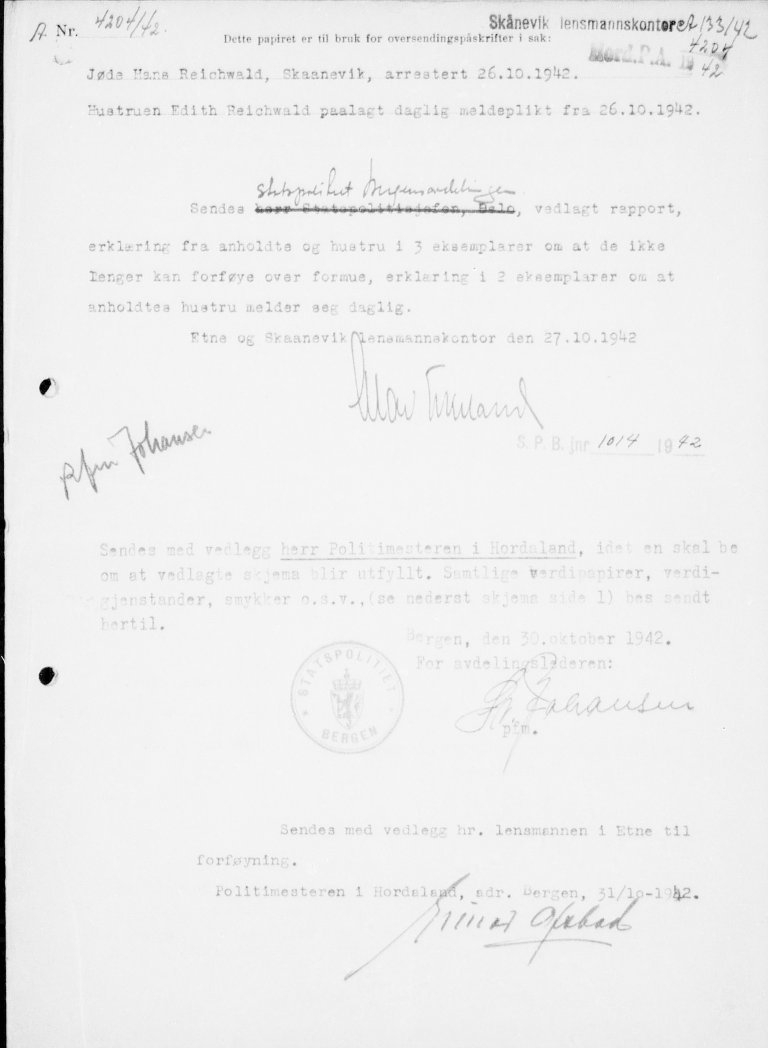

Sheriff’s Report on the Arrest of Hans Reichwald

In a report to the Chief of the State Police in Oslo, written the day after the arrest, the sheriff of Etne and Skånevik, Olav Ekeland, described how Hans Reichwald was apprehended. The report provides a detailed account of how the arrest was carried out, what instructions were issued, and the consequences for Hans and his wife Edit.

A Phone Call from the State Police

On October 25, the sheriff received a phone call from the Bergen division of the State Police. He was instructed to report to the Ortskommandantur in Etne at 5 a.m. the following morning to receive an arrest order. According to the directive, Hans Reichwald was to be arrested at 6 a.m. that same day. His wife, Edit Reichwald, was to be placed under daily reporting requirements, and the couple’s possessions were to be confiscated.

The Arrest and Transfer

The sheriff traveled to Skånevik with a German non-commissioned officer and carried out the arrest. Although the original order specified transport to Bergen, Hans was instead transferred to the Haugesund Police Department. This change was made in consultation with the chief of police in Haugesund, who noted that Hans would be forwarded “along with similar transports from Haugesund.”

For practical reasons, Edit was not placed under reporting requirements with the sheriff in Etne, but rather with the mayor and local NS leader in Skånevik, Kristoffer Tungesvik.

Confiscation of Property

On the same day as the arrest, the couple was required to sign a declaration stating that they could no longer “dispose of” their assets and belongings. All items in their home were inventoried and recorded.

The couple rented a two-room apartment with a kitchen in the home of Reinert Vannes. The furnishings included furniture, kitchenware, and a number of silver items, among them 19 silver forks, 10 silver spoons, 2 serving spoons, 2 knives, and 16 assorted silver table pieces.

The bedroom contained a double bed, a crib, a vanity, a wardrobe, and bedding. The kitchen was equipped with an electric stove, a changing table, and utensils appropriate for a small household. A bicycle was also registered, along with a bank account and a silver box containing jewelry at the Skånevik Savings Bank. The jewelry included a gold ladies’ watch with chain, a platinum bracelet with seven diamonds, three diamond rings, a diamond pin, and a silver and enamel cigarette case.

Hans also operated a mechanical workshop, which was affected by the confiscation.

Missing Items at the Time of Transfer

Following the arrest, the sheriff was informed that Hans was to bring identification papers, ration cards, and eating utensils. The latter were missing at the time of transfer.

On the following page, it states:

“After receiving the case, Edith Reichwald has left Skånevik for Stavanger, in accordance with what is noted in document 8 (dok. 8).”