Martin Wølstad and his work crew in the Klondike, 1898. Photo by Asahel Curtis.

Martin Wølstad – A Klondike Gold Prospector

What drives a young man – just sixteen years old– to leave behind his parents, siblings, and home to venture out into the world? As part of the 2025 Year of Migration, we’re sharing the story of Ole Martin Vølstad, the son of a farmer from Tasta, just outside Stavanger, who became a gold prospector in the Klondike region of Canada. During his time abroad, he Americanized his name to Martin Wolstad. Upon returning to Norway as a Norwegian-American, he became known as Martin Wølstad.

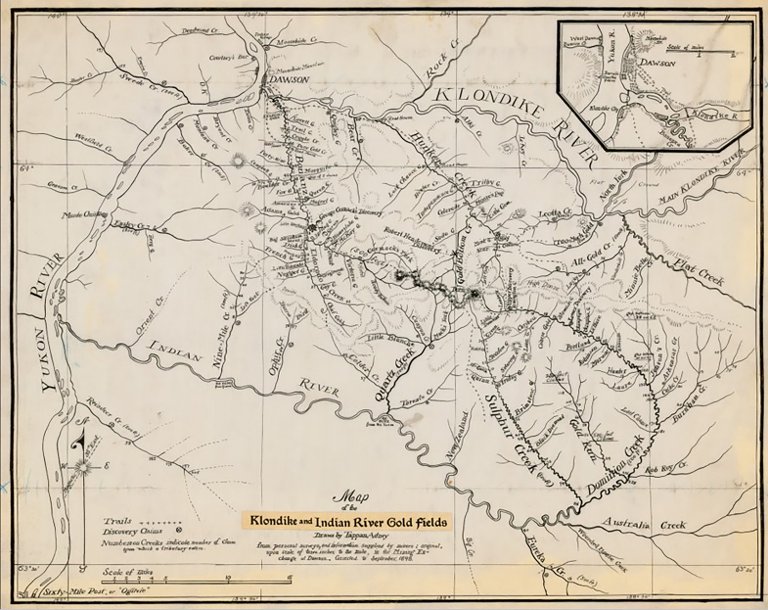

On August 16 1896 a major gold discovery in the Klondike region of Yukon, Canada, made headlines around the world. The news sparked what would become known as the Klondike Gold Rush – a feverish migration of thousands of hopeful prospectors. Many sold everything they owned in pursuit of fortune, only to be met with the region’s harsh climate, unforgiving wilderness, and grueling physical demands. As this story shows, arriving early in the Klondike was often the key to success.

Martin Wølstad, the subject of this migration story, was in the right place at the right time. In 1893, rumors of gold in Yukon reached him, and he acted fast. Today, we know that he struck it rich, finding significant amounts of gold and becoming a wealthy man. A photo album documenting his time in the Klondike became a treasured keepsake – both for him and for the generations that followed.

The album, filled with photographs from his time in the Klondike, was likely put on display many times and shows signs of wear. Today, the binding is no longer intact, and the pages exist as loose sheets with mounted photographs. The images include work by well-known photographers such as Eric A. Hegg, Arthur C. Pillsbury, and Asahel Curtis. They captured scenes of Martin, fellow prospectors, Indigenous peoples, and key moments from the gold rush community. These photographs can now be explored in detail through Digitalarkivet.

Three Photographers

The rumors of gold discoveries and the flood of hopeful fortune-seekers heading to the Klondike also drew photographers to the region. One of them was Swedish-born Eric A. Hegg (1867–1947), who captured the iconic image of crowds of people struggling to cross the Chilkoot Pass. Hegg ran a photography studio in Dawson City with his business partner, Per Edward Larss. It’s likely that Martin purchased several of the photographs in his album from their shop. Hegg documented both individuals and locations tied to the gold rush, and more than half of the photos in Martin’s album are attributed to him.

Asahel Curtius (1874–1941) was another prominent Klondike photographer. He arrived in 1897 to documentthe gold rush and, in addition to taking photographs, also worked as a prospector. Curtis became known for his compelling portraits of gold miners. It’s possible that Martin Wølstad and his crew hired Curtis to take their photos—he captured images of Martin and his colleagues at the claim he operated with a partner named Sanderson.

The third photographer represented in Martin Wølstad’s album is Arthur C. Pillburg (1870–1946). In addition to his work behind the camera, Pillsbury was also an inventor of photographic equipment. He is credited with building the first rotating panoramic camera.

Ole Martin Vølstad was born in December 1872 and baptized two weeks later. He was likely named after his parents, Ole and Malene, and was their sixth child. He grew up on a farm in Tasta, just outside Stavanger, with five older and four younger siblings.

His three oldest brothers – Thore, Fredrik, and Olaus – were all born in Gjesdal, where Ole Martin’s parents had lived during the early years of their marriage. In 1860, the family moved to a farm in lower Tasta, and their household grew significantly. The year before Ole Martin was born, his sister Berthe Karine arrived, followed by several more siblings in the years to come.

By the time Ole Martin was confirmed at around fifteen years old in the fall of 1887, he was the older brother to four younger siblings: Thorvald Andreas, Marie, Olaf, and Secilie Margreta. A foster daughter, Marie, also grew up with the family. She was the daughter of Ole Martin’s eldest sister, Elen Severine, who had married the year before his confirmation. Marie was only a month old when her mother passed away.

A Brother in America

Ole Martin’s brother, Olaus, went to sea shortly after his own confirmation, leaving behind his family and his then one-year-old brother. His first voyage aboard the ship Vestlandet took him to America, followed by trips to Antwerp and England. He also spent time in London and Hamburg, where he signed off. Later, he sailed to Rio de Janeiro and disembarked there in 1882.

According to the seamen’s roll, Olaus received permission to emigrate to America on February 17, 1883. Immigration records from Ellis Island show that he was a passenger on the SS Poland, which arrived in New York from Copenhagen in March 1883. His stated destination was Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The national census of 1891 shows that several of the Vølstad children, including Olaus and Ole Martin, were no longer living at home. Family history tells us that Ole Martin, at the age of sixteen, left for America in 1889 to search for his older brother. Although they hadn’t grown up together and likely didn’t have a close personal bond, Olaus may still have been an important figure to Ole Martin. Perhaps he inspired his younger brother to explore the world. Or maybe Ole Martin’s journey was driven by a desire to find Olaus, from whom the family hadn’t heard in a long time. It’s possible both reasons played a role.

A rather worn immigration immigration log for the port of New York, with parts of the paper illegible, shows that Ole Martin disembarked in America for the first time on May 23, 1889. He had traveled via Liverpool on the steamship SS City of New York. He reportedly slept on a jute sack during the crossing.

Ole Martin Vølstad is listed in the log as Martin Volstad. He kept the first name, which worked well in English and several other European languages, and replaced the letter 'ø' in his last name with 'o'. Over time, he also began spelling his last name with a 'W'.

Various Jobs on the West Coast

Martin was fortunate with the timing of his journey to America. Based on his own notes and stories told to family members, we know that he initially stayed in the western regions and did various jobs. He worked as a sawmill laborer in Tacoma on the Pacific coast, then moved on to Chilkoot Inlet in Alaska, where he was a salmon fisherman. Later, he traveled further south to Juneau, where he worked for four years in mines extracting gold-bearing quartz.

A Challenging Journey from Alaska to Canada

In January 1894, Martin left Alaska. Together with a man from California, he set out for the Yukon and the Klondike River. They brought food and supplies to last for two years. The first part of the journey was by boat up the Alaskan coast, then they traveled inland towards the mountain pass he referred to as 'Th Sommet'. According to his own descriptions, it was about 30 English miles to the top, and the terrain was 'very steep and difficult to traverse'. It took them two months to get over the pass with all their equipment.

After crossing the mountain pass and reaching the top, Martin and his companion from California continued towards the Klondike area. However, they still had a long journey ahead of them. At a bay by Lake Bennett, they and several others stayed for about two months. They needed a boat to cross the lake, which they had to build themselves. They felled trees and sawed them into planks to construct a 30-foot-long, 6-foot-wide flat-bottomed boat. It took about a month to complete the boat, and then they had to make it watertight. They cut holes in the ice on the lake to allow the boat to swell. After a few weeks, they were able to continue their journey. They passed the notorious Whitehorse Rapids and Miles Canyon, where all their equipment had to be carried overland. In June 1894, they reached Circle City. Before the Klondike Gold Rush, this was the largest town on the Yukon River. It was established in 1893 as a supply point for gold miners at Birch Creek, but it eventually became a hub for gold mining activities in the area.

Circle City in the Yukon Area

We know little about Martin's time in Circle City, but we assume that this is where he gained experience and learned the technique known as 'Placer Gold Mining'. Unlike extracting gold from solid rock, where it is extracted, this technique involves separating gold from sand and gravel. The simplest method is to use a gold pan with a mixture of sand and water. When the pan is swirled around, the gold settles at the bottom.

To extract gold-bearing sand, it had to be dug up. This was done in the winter when the ground was frozen. At night, fires were lit to melt the ground a few meters down to the gold-bearing layer, which could then be dug up during the day. In the summer, the work of separating sand and gravel from the gold was done using water. Using a gold pan was slow. When the sand piles were large, it was faster to sluice a mixture of sand, gravel, and large amounts of water through sluice boxes, which had crosswise riffles where the gold settled at the bottom.

Circle City was emptied of gold miners within a few days when the major gold discovery in the Klondike became known. The usual travel route was on the frozen Yukon River with sleds and dogs. Martin likely traveled to Dawson in February 1897.

In the article "A Gold Miner Tells" in the Jarlsberg and Laurviks Amtstidende on August 27, 1897, a Mr. Hestwood stated: When the great riches in Bonanza Creek were discovered, people flocked from all around; the town of Circle City, which previously had about 2000 inhabitants, now practically no longer exists, and the demand for sleds and dogs to get over the mountains was so great that many paid 1000-1800 Norwegian kroner for such a means of transportation.

No Reunion Between the Brothers?

As far as we know, Martin never found Olaus. We have also been unable to find archival records that can provide any answers about what happened to him after he disembarked in New York in 1883.

We know that Martin did well as a gold prospector in the Klondike. His success began when he and an Englishman, Daniel Sanderson, acquired a claim they believed in. It was located in what was called French Gulch, near the very rich claims Eldorado No. 16 and 17. It measured 60x180 meters, and they named it French Gulch No. 0.

Martin and his partner, Daniel Sanderson, applied for permission to mine the claim and received approval in December 1897. The winter and spring of 1898 were spent digging up as much as possible. They had several paid helpers to carry out the work. The pile of sand and gravel grew throughout the winter and was ready for washing in the summer.

Photographer: Asahel Curtis.

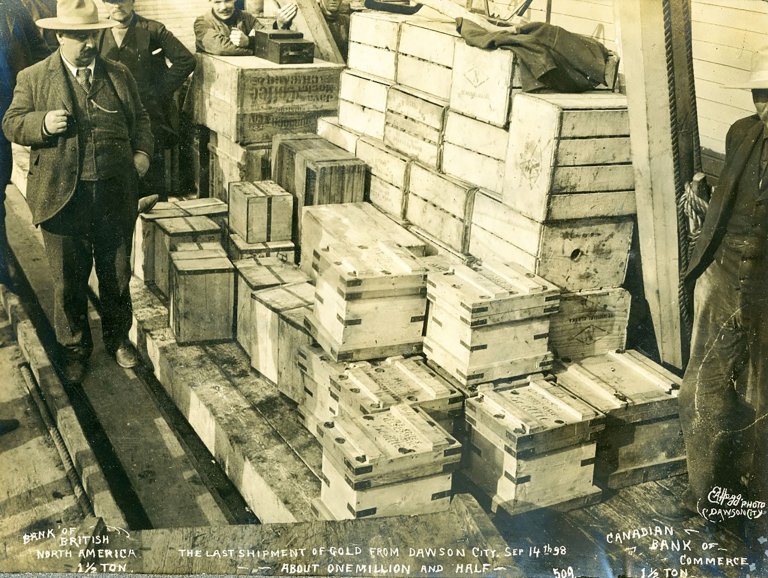

To San Francisco

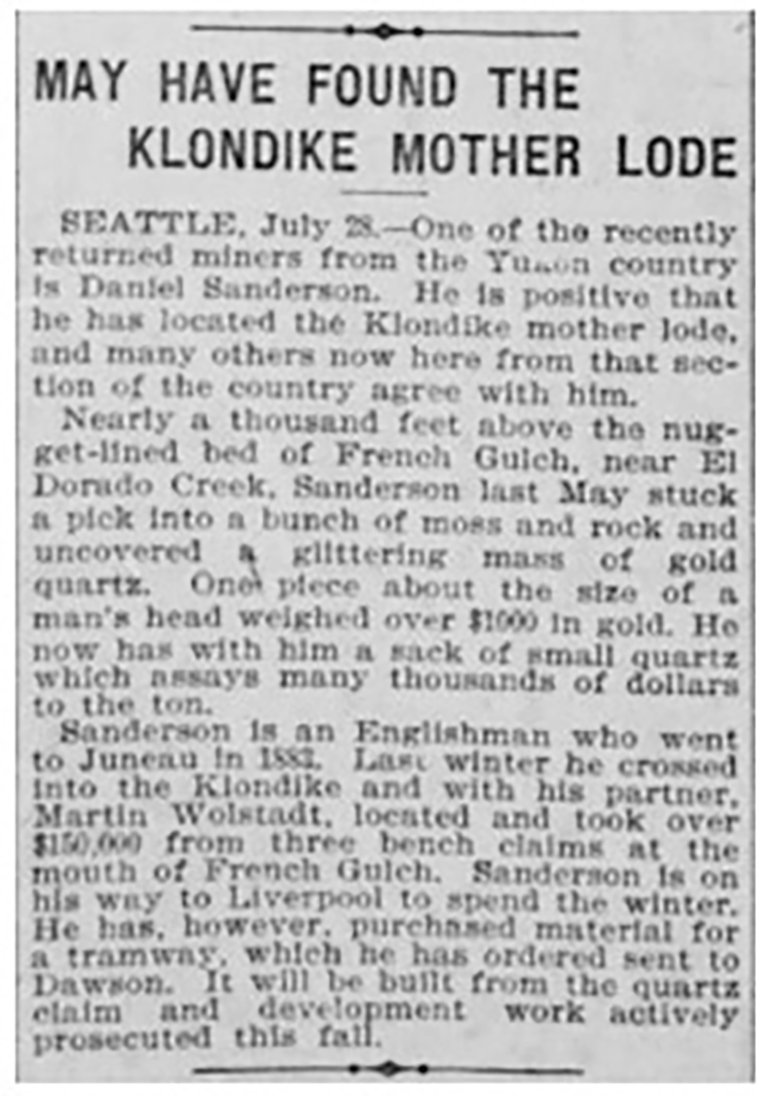

Martin and Daniel left the Klondike in 1898. On July 29, an interview with Daniel was published in the San Francisco Call. He stated that he and his partner Martin had found gold worth $150,000 in the claim. Under the headline: 'May have found the Klondike mother lode,' it read:

One of the recently returned miners from the Yukon country is Daniel Sanderson. He is positive that he has located the Klondike mother lode, and many others now here from that section of the country agree with him.

Nearly a thousand feet above the nugget-lined bed of French Gulch, near El Dorado Creek, Sanderson last May stuck a pick into a bunch of moss and rock and uncovered a glittering mass of gold quartz. One piece about the size of a man's head weighed over $1000 in gold. He now has with him a sack of small quartz which assays many thousands of dollars to the ton.

Sanderson is an Englishman who went to Juneau in 1883. Last Winter he crossed into the Klondike and with his partner, Martin Wolstadt, located and took over $150,000 from three bench claims at the mouth of French Gulch. Sanderson is on his way to Liverpool to spend the Winter. He has, however, purchased material for a tramway, which he has ordered sent to Dawson. It will be built from the quartz claim and development work activity prosecuted this fall.

Martin returned home to Tasta in the fall of 1898 but went back to America again just after New Year's in 1899. He then sold his claim and ended his gold mining life in Canada, allowing him to settle in his hometown as he had decided.

Of the approximately 100,000 people who wanted to try their luck as gold miners in the Klondike, only about 30 percent managed the arduous journey there. During the three years of intense gold mining activity, around 13 percent found gold [1]. Martin was among the lucky ones.

Photographer: Eric A. Hegg.

Sources:

[1] Larsen, F. (2023). The Klondike Gold Rush, Aftenposten History, 2023(4), 53-63.

Article in the San Francisco Call

A bit more about the photos in Martin’s album

More than a quarter of Martin’s photo album features images of Indigenous peoples and their lives in the Yukon. The Tlingit were especially known for their Chilkat woven robes, carved totem poles, and other traditional crafts. Some of the photographs in the album also depict Tlingit Potlatch ceremonies.

Back in Norway, his fiancée Inger Roth was waiting for him. Martin and Inger got married on Thursday, June 14, 1900. His brothers, Thore and Fredrik, were the witnesses. Many guests were invited to the celebration in their new house.

The photo is privately owned but has been approved for publication in this online exhibition.

Theft during the wedding celebration

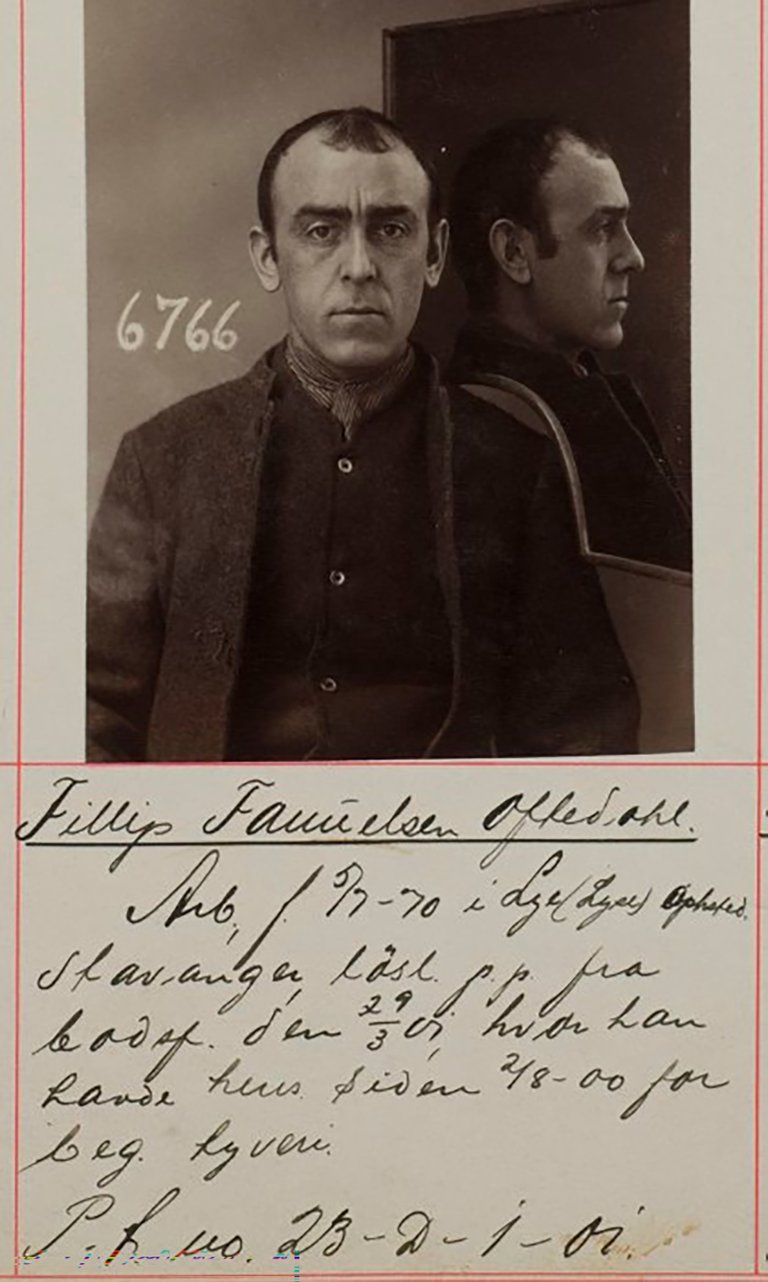

It was well known both in the family and the local community that Martin Wølstad had become wealthy from gold prospecting. The day after the wedding celebration, he discovered that several valuables, including a gold nugget, had been stolen. When he reported the theft to the police, he named his cousin, Filip Oftedahl, as the suspected perpetrator.

The theft was covered by several newspapers across the country. On June 16, the entire incident was detailed in Stavanger Aftenblad under the headline: 'The Grand Theft. The Suspect Arrested. The Bank Book, Securities, and Gold Recovered.' The introduction also captured the unusual nature of the event: The mysterious grand theft at Klondike man Martin Wølstad's place was naturally the only topic of conversation throughout the city last night when 'Aftenbladet' came out with the sensational news.

Filip Oftedal was found guilty. He was sentenced to twelve months of hard labor for the crime and sent to Botsfengselet in the capital. The verdict was delivered on July 26, about five to six weeks after the theft. Martin recovered almost everything that had been stolen, except for 20 kroner that Filip had spent on beer and transportation. After serving several prison sentences, Filip chose to emigrate to America in 1906, citing 'low earnings' as the reason for his departure.

Klondike in Tasta

In the 1900 census for Hetland, Martin's occupation was listed as 'Wealth.' However, it also showed that there was some activity on the farm. They had planted potatoes or sown grain that was harvested. Additionally, they had an orchard and some animals. The property was referred to as 'Klondike' and 'Klondyk' in both the mortgage register and the fire insurance appraisal register. It is most likely that Martin decided on this name. In the registered division of property where Martin was present, it is stated at the end 'that the assessed parcel should be called 'Klondik.''

By 1910, Martin's occupation was listed as 'merchant.' He and Inger had become parents to eight children, and they had a nanny and a maid living in the house. Among the children were two sets of twins. Ten years later, Martin was listed as 'annuitant' and father to eleven. He and his wife remained at Klondike in Tasta for the rest of their lives. In the local community, he was known as 'Gullmaen' (the Gold Man).

About the Online Exhibition

This migration story was written by Senior Advisor Hanne Karin Sandvik, in collaboration with First Archivist Ine Fintland and Archivist Synnøve Østebø.

Key contributors also included Martin Wølstad Jr. and Hans Ivar Sømme.

The article was originally written in Norwegian and translated into English using Copilot, based on the prompt: “Translate idiomatically for an American audience. The article will be published on the website of the National Archives of Norway. Use terminology appropriate for a U.S. readership, and ensure the language is clear and concise.” The final version was reviewed and edited by Ine Fintland and Kayla Marie Tungodden (Senior Advisor) for clarity and accuracy.

Some of the Sources

In this online exhibition, we’ve used the following types of historical sources:

- Parish records to find information about baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and deaths.

- Census records to get an overview of who lived together and where they were residing.

- Mortgage registers and deed books to trace registered purchases and sales of properties

- Seamen’s rolls and to learn more about individuals who signed on to ships and sailed abroad.

Archival records that describe the theft and its consequences

Verdict

Issued against Shoemaker Filip Fanuelsen Oftedal on July 26, 1900, charged with theft for the fourth time

The Public Prosecutor for Lister og Mandal and Stavanger District Court, in a decision dated July 13 and served on the 19th of the same month, indicted Filip Fanuelsen Oftedal under Penal Code Chapter 19, §1 in conjunction with §7, subsection 2(b), for having previously been convicted of theft on three occasions. On June 14, 1900, without the owner's consent and with the intent of unlawful gain for himself or others, he removed from the Tastad farm in Hetland a cash box belonging to Martin Vølstad. The contents included:

- a passbook from Stavanger Privatbank

- various securities totaling NOK 130,188

- some unprocessed gold worth approximately NOK 800

- and about NOK 1,100 in cash.

The case was handled in accordance with §373 of the Criminal Procedure Act. Based on the defendant’s full and unconditional confession – corroborated by witness testimony – the court found sufficient evidence to convict him as charged.

The defendant is therefore found guilty of repeated theft under Penal Code Chapter 19, §1 in conjunction with §7, subsection 2(b), and is sentenced to 12 months of hard labor. In determining the sentence, the court considered both the high value of the stolen items and the defendant’s prior criminal record. However, it also took into account that the financial loss to the victim was relatively minor, as nearly all the cash and securities were recovered – except for about NOK 20. The time the defendant spent in pre-trial detention was also considered.

No claims for damages were submitted, and no court costs were incurred by the defendant.

The Court Rules:

Filip Fanuelsen Oftedal is sentenced to 12 months of hard labor for repeated simple theft under Penal Code Chapter 19, §1 and §7, subsection 2(b).

The sentence is to be carried out under the direction of the prosecuting authority.

The verdict was read aloud to the defendant, who accepted it. He was then handed over to the officer on duty for transfer to custody.

The court session lasted three hours.

Signed:

Gabrielsen (acting), Rasmus A. Kydland, O. C. Høiland

In fide: Gabrielsen (acting)