A New Life in Uncertain Times: Ingeborg Gullestad’s American Story, 1928–1930s

What happens when the world economy collapses, and you find yourself alone in a foreign country – young, newly arrived, and full of hope for a better future? In 1928, Ingeborg Gullestad left Kvinesdal for America, just as many young women and men had done before her. America was seen as the land of opportunity. But only a year later, the stock market crash plunged the country into the Great Depression, and Ingeborg lost her savings. Through just a few private letters and some photographs, the archival records offer us a glimpse into her life as an immigrant in New York and Chicago during the 1930s.

From Kvinesdal to New York: One Young Woman’s Journey

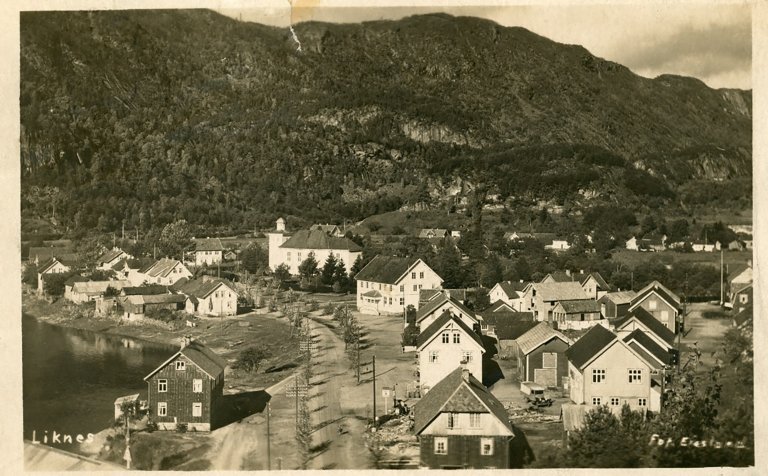

In April 1928, seventeen-year-old Ingeborg Mathilde Gullestad left left the small village of Kvinesdal – home to about 3,000 people – for the bustling metropolis of New York, then a city of nearly seven million. This was not just a dramatic change in scale – New York had about 2,300 times as many people – but an encounter with an entirely new reality. From a childhood on a farm surrounded by fields and mountains, in a community where most faces were familiar, Ingeborg stepped into a world of skyscrapers, crowds, and a new language. It was a shift in culture, language, and way of life. She left the rural and familiar behind for the urban and unknown.

Visa and Departure: A Last-Minute Decision

Ingeborg’s journey came together on short notice. Her brother Hans had planned his trip much earlier, securing his ticket and visa just over two months before departure. For Ingeborg, there was far less time to prepare. Her parents believed it would be safer for her to travel with her brother and their cousin, Ingvald Berntsen Gullestad, rather than making the journey alone later on.

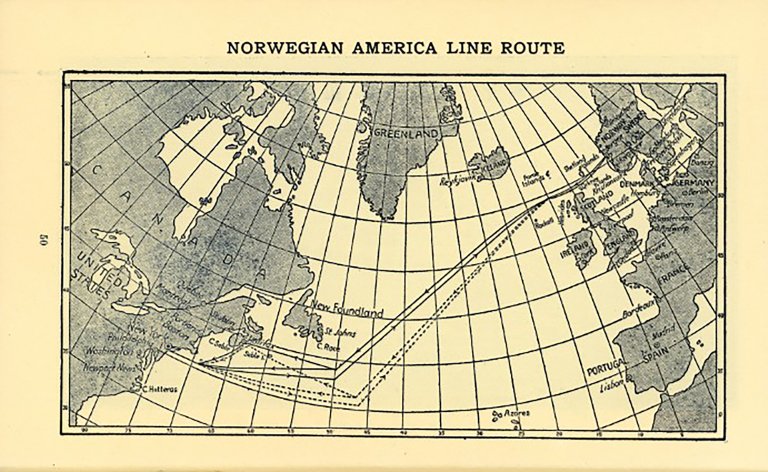

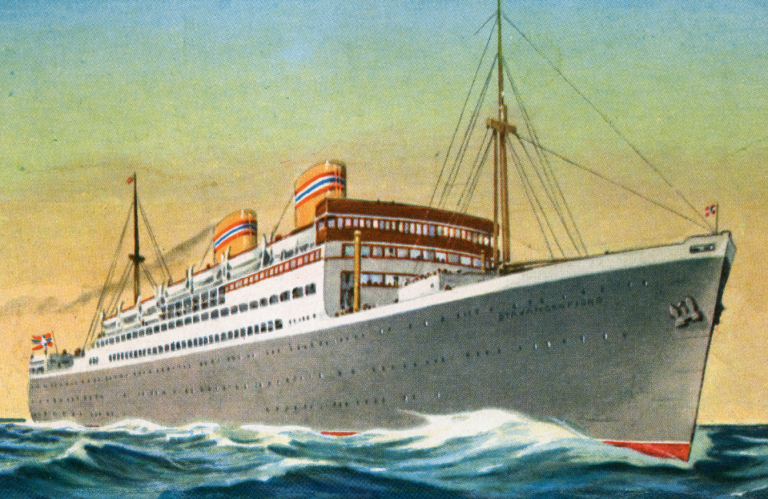

This meant she first had to travel to Oslo to obtain a valid visa before the April 13 departure date. Ingvald also left from Oslo, and the two boarded the ship Stavangerfjord there. Hans joined them in Stavanger the following day. Nine days later, the three of them arrived in New York.

Their eldest sister, Anne Kristine, had already lived there for three years, and their brother Selmer Emil had also recently made the journey. The distance from Kvinesdal to New York was immense – over 7,000 kilometers in a straight line, and roughly 9,000 kilometers by sea. The Stavangerfjord crossed the Atlantic north of the British Isles, adjusting its course for weather, ocean currents, and port stops.

The only way the four siblings could keep in touch with their family back home was through letters.

Immigration Papers: Who Was Ingeborg When She Arrived in America?

Neither Hans nor Ingeborg had ever been to America, and neither spoke a word of English. According to the American immigration papers, both could read and write Norwegian and were in good physical and mental health. They had blue eyes and blond hair; Ingeborg was 5 feet 7 inches tall, and Hans was 5 feet 10 inches. Hans was listed as a “Laborer,” Ingeborg as “Domestic.” Both had paid for their own passage and brought $25 with them.

Both Hans and Ingeborg stated that they were going to their sister Kristine, but gave different addresses for her in Brooklyn: Hans wrote 256-19 Street, while Ingeborg listed 3098 Bedford Avenue. This suggests Kristine may have moved that spring – perhaps between February and April, when her siblings applied for their visas.

Kristine: The First to Leave

On April 18, 1925, Kristine boarded the Stavangerfjord and left Norway behind. Ten days later, she arrived in New York – just eighteen, alone, and hopeful for work and opportunity. According to her immigration papers, she could read and write Norwegian but spoke no other languages. She had brown hair and brown eyes, was unmarried, and had paid for her own ticket. Her occupation was listed as “housework,” and her destination was Brooklyn, where she planned to stay with her friend Anna Nilsen. Norwegian migration records note “low earnings” as the reason for her departure.

When Kristine left, Ingeborg was 14, Hans nearly 18, and Selmer 16. The two youngest siblings, Rakel and Astor, were almost 11 and 9. Kristine’s decision and experiences influenced her younger siblings. In Brooklyn, she adapted quickly –learning the language, making friends, and finding work. Her letters home likely painted a picture of opportunity and security in her new country.

The Family Back Home in Norway

Three years later, Ingeborg, Hans, and Selmer decided to seek their fortunes in America – just as their older sister Kristine had done before them. Back on the family farm, only two siblings remained: Rakel (14) and Astor Olaus (11). They were still in elementary school and helped their parents, Hans Asinius and Oline Margrete, now 56 and 42 years old, with the farm work.

Ingeborg’s Early Years: A Childhood Shaped by Loss

Ingeborg was born in 1910, the middle child in a family of seven – three older and, eventually, three younger. At the time of her birth, her father was nearly 39 and her mother 25. In the Norwegian national census of December 1 that same year, she was recorded as an "unbaptized girl".

Ten years later, the household consisted of her parents, Hans Asinius and Oline Margrete, and six children: Kristine (14), Hans (13), Selmer (12), Ingeborg (10), Rakel (6), and Astor (4). Although most family members had double names, they typically used only one in daily life.

Although the family officially counted seven children, Ingeborg’s early memories were marked by the absence of one: her sister Rakel. The first Rakel – the fifth child – died in infancy, before the two youngest were born.

A Profound Loss: Her Sister Rakel

One of Ingeborg’s earliest and most formative memories was the loss of her younger sister Rakel, who died of whooping cough whooping cough at just four months old. Like Ingeborg, Rakel had been baptized on their father’s birthday – Christmas Day.

Ingeborg vividly remembered the loneliness she felt in the attic when her mother asked the three oldest children – Kristine, Hans, and Selmer – to come downstairs and say goodbye to the baby. Ingeborg was told she was too young to see her deceased sister and was left alone, grappling with questions no one would – or could – answer.

Liknes School

Ingeborg started first grade at Liknes School on October 3, 1918. The class had 17 pupils – eight girls and nine boys. Half of the girls came from farming families; the others had fathers who worked as a carpenter, laborer, baker, or tailor. Among the boys, some were sons of farmers, while others came from families of bakers, factory workers, general store owner, and operations manager.

During the twelve-week school year, eight pupils – nearly half the class – came down with whooping cough. Ingeborg was spared, but the illness was not unfamiliar to her. While her classmates recovered and returned to school, Ingeborg already knew that illness didn’t always pass – it could take lives.

Front row, from left to right: Reidun Gullhav, Lovise Egeland, Inga Aamodt, Johanne Aamodt, Sally Aamodt, Liv Lorentsen, Judith Mydland, Elma Tranberg, Hanna Verås, Hedvig Gullestad, and Anna Johannessen.

Second row, from left to right: Teacher Torkel Verås, Kristen Flaten, Johan Tranberg, Jakob Aamodt, Albert Aamodt, Hartvik ?, Jens Rødland, Torleiv Rafoss, Sigurd Husefjeld, Torvald Faret, Norman Larsen, Martin Hamre, Harald Hansen, and Trygve Årstøl.

Third row, from left to right: Syvert Hunsbedt, Arne Moland, Samuel Aamodt, Anton Regevik, Margrete Gullestad, Grete Egeland, Anna Rødland, Dagny Eide, Ingeborg Gullestad, Lilli Brauland, Palma Larsen, Nils Egeland, Georg Regevik, and Teacher Peder Rygg.

Schooling and Subjects

In second grade, the pupils studied the first part of the catechism and the biblical story of Moses’ birth. In addition, they had reading, arithmetic, and time for play. The school year lasted twelve weeks.

In third grade, which lasted fourteen weeks, Ingeborg was present almost every day – only three days were recorded as sick leave. The class read from the New Testament, covering stories up to the Ascension of Jesus, and reviewed the beginning of his ministry. They learned about King Haakon Haakonsson of Norway, and in geography, the focus was on Norway. In singing lessons, they practiced both hymns and songs such as Ja, vi elsker, Deilig er den himmel blå, and Alle fugle små. In arithmetic, they worked through the textbook from page 11 to 29. The teacher was Tollak Eiesland.

In fourth grade, Ingeborg attended school with 24 other pupils –12 girls and 13 boys. The school year lasted fourteen weeks. They continued reading from the New Testament and learned about King Sverre of Norway in history. In science, the focus was on the human body, and they also received a brief introduction to electricity. In geography, the theme was Europe. The teacher was T. Verås, who had also taught them in first grade.

Confirmation and New Horizons

In the fall of 1925, the same year her sister Kristine left for America in the spring, Ingeborg was confirmed. By the time she herself emigrated to the United States in the spring of 1928, she had completed five years of primary school. In her migration papers, she stated “better earnings” as her reason for leaving – more or less the same explanation Kristine had given three years earlier.

In addition, she knew that her sister had settled well in New York. Kristine had learned English, found a job, and secured a good place to live. She had also made new friends, and several others from Kvinesdal had already made the journey. For Ingeborg, it wasn’t just the hope of finding work – it was also the chance to follow in the footsteps of someone who had already shown that it was possible.

A New Life in Brooklyn

When Ingeborg arrived in the United States in the spring of 1928, the country was in the midst of what would later be called the Roaring Twenties. The era was marked by economic growth, rapid social and cultural change, and widespread optimism. At the time, Calvin Coolidge (1872–1933) was president, known for his laissez-faire approach to governance, which had significantly strengthened the U.S. economy.

In major cities like New York, there was a fast pace, fresh impulses, and a strong belief in the future. It was in this atmosphere that Ingeborg settled in Brooklyn with her sister Kristine and began her new life.

Working Life in the Big City

Ingeborg took on various jobs – first as a nanny and housekeeper, later including positions as a secretary in medical and dental offices. Her everyday life was shaped by adaptation, work, and new friendships.

Starting out, it was challenging challenging to navigate a new language, but she learned quickly – especially from the mistakes she made.

The children in the family she worked for became important teachers, and they laughed heartily when she confused the words “flies” and “flowers,” asking them to close the windows so the flowers wouldn’t come in. Moments like these were both funny and helpful – she remembered especially well when linguistic misunderstandings led to laughter.

Stock Market Crash and New Challenges

In March 1929, Herbert Hoover (1874–1964) became President of the United States. He promised to continue the economic policies of his predecessor, Calvin Coolidge, and declared that America was closer than ever to eliminating poverty.

This optimism ended abruptly in October 1929, just a year and a half after Ingeborg Gullestad arrived in New York. On October 29 – known as Black Tuesday – the stock market collapsed, triggering an economic crisis that affected every part of American society and had a profound impact on the global economy. For many, the crash meant losing jobs, homes, and financial security.

Ingeborg experienced this crisis firsthand. She lost all her savings, but managed to get by because she had no debts or dependents. She knew people who lost everything, and some who never fully recovered. At the same time, she saw others who managed to get through, thanks to financial resources, strong networks, or simply luck. For many, survival required major personal adjustments, hard work, and perseverance.

For a period, Ingeborg’s own situation was uncertain. Yet she demonstrated resilience and adaptability, finding new opportunities even in difficult times.

The Depression Era and Moving to Chicago

In the early 1930s, Ingeborg and her sister moved from Brooklyn, New York, to Chicago, where their brother Hans was also living. The move was motivated by the hope of finding work during a time marked by high unemployment, social unrest, and economic uncertainty.

In Chicago, the gangster Al Capone – “Public Enemy No. 1” – was a well-known figure. Ingeborg later recalled that, while living there, she saw Al Capone driving through the city. He was both feared and admired, and the sight of him left a lasting impression on her.

May 17, 1931 is written on the back of this photograph of Ingeborg and Kristine.

Challenges and Opportunities

For Ingeborg, this decade was marked by contrasts – financial loss and personal adaptation, but also work, community, and new experiences. Eventually, she moved back to New York.

Ørkenen Sur – A Hardship Ingeborg Was Spared

Ingeborg knew that not all migrants fared as well as she and those she personally knew. Even before the Great Depression, a community of destitute Scandinavian immigrants had formed in New York, known as Ørkenen Sur. This area was located in the harbor district of Red Hook in Brooklyn – the neighborhood where most Norwegians had settled – and existed for about ten years, from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s.

Red Hook was originally intended for railroad use, but was left undeveloped and eventually became a dumping ground. Here, among scrap metal, abandoned boats, and rusty barrels, a makeshift community emerged, where homeless and unemployed Scandinavians – mostly Norwegians – struggled to survive. At its peak, as many as 500 people may have lived in Ørkenen Sur.

A New Era: The New Deal

In 1933, a political shift occurred: Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945) became president after Herbert Hoover, who had been reluctant to intervene during the crisis. Roosevelt launched the New Deal, a policy in which the government took an active role in creating jobs and stimulating the economy. He promised “a new deal for the American people” and to improve the lives of what he called “the forgotten man.”

Ingeborg and Kristine witnessed how Roosevelt’s initiatives gradually changed the cityscape and daily life. They saw how public works projects brought new activity to the streets, and how hope for the future gradually returned.

A City in Transformation – New York’s Skyline Grows

During the years Ingeborg lived in New York, the city changed dramatically. The most visible symbol of this transformation was the construction of the Empire State Building, completed in 1931. With its 102 floors and a height of 1,250 feet, it was the tallest building in the world. It was so tall, the entire center of Kvinesdal could have fit inside – stacked one floor above another!

Several other iconic buildings were also built during this period: the Chrysler Building (77 floors, completed in 1930), Rockefeller Center (construction began in 1930), Radio City Music Hall (opened in 1932), and the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel (opened in 1931). These buildings transformed the cityscape and made New York a symbol of modernity and optimism for the future, recognized around the world.

Leisure and Community

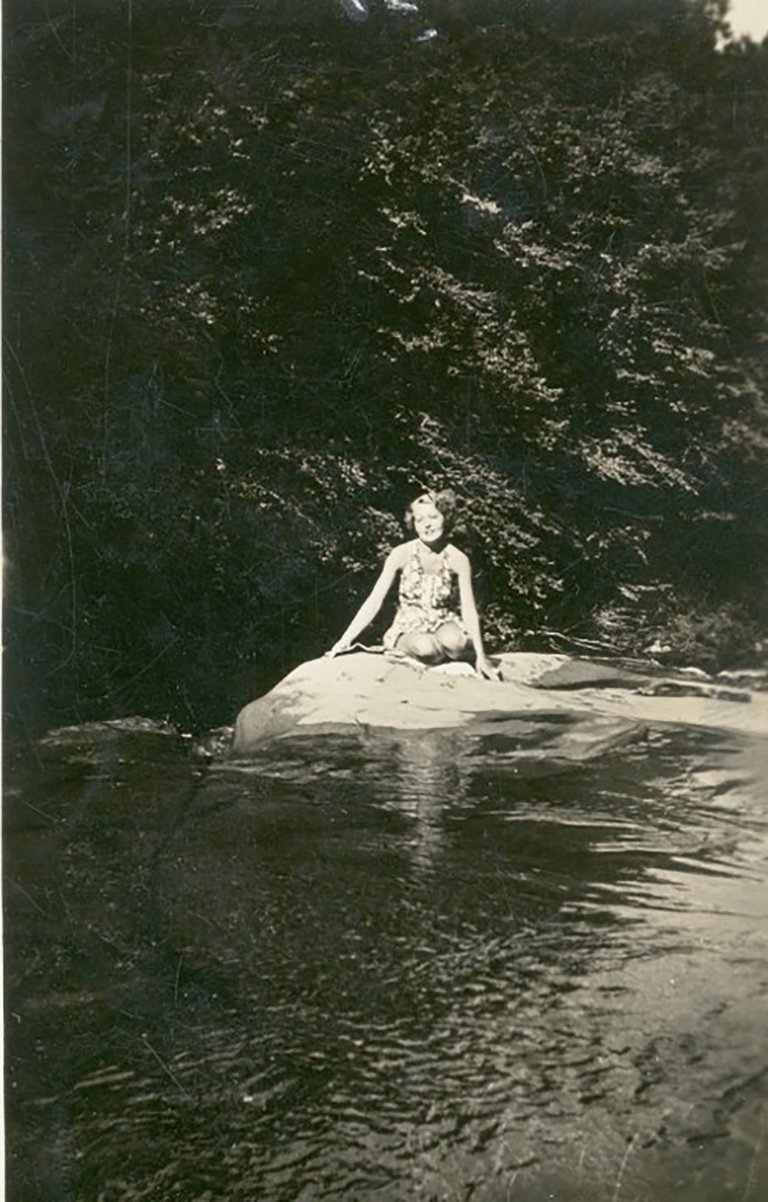

Although everyday life in New York was centered around work, there was also time for leisure – often spent at the beach or in a park.

Ingeborg managed well through the crisis, and the photos from this period show a young woman who found her place in the big city. She was eager to learn, fashion-conscious, social, and adaptable.

A Portrait of Significance – Ingeborg Gullestad at Vang Studio

In the 1930s, many Norwegian immigrants in New York sought to have their portraits taken. Having one’s portrait taken was a way to demonstrate – to oneself and to others – that one was doing well: that one possessed dignity, style, and promising prospects. Through photography, it was possible to establish a new identity while affirming one’s ties to both Norwegian heritage and American society.

One name stood out among those seeking portraits of quality and distinction: Knut Vang. The Norwegian-born photographer opened his own studio in Brooklyn in the late 1920s, just a few years after emigrating from Norway. He quickly became a central figure in the Norwegian-American community. Combining technical mastery with an artistic eye, he documented everything from celebrations and theater performances to portraits of prominent Norwegians such as Roald Amundsen, Fridtjof Nansen, and aviation pioneer Thor Solberg, whom he both photographed and filmed in Brooklyn. His work was exhibited and awarded in American photography shows, and he became known as the person to contact for “a truly exceptional photograph”

In 1932 and 1933, Ingeborg Gullestad chose to be photographed at Vang Studio – a decision that reflects awareness, ambition, and a desire to be seen through the lens of the finest Norwegian-American photography. The portraits show a woman firmly rooted in her new life, dressed in contemporary fashion, her gaze steady and self-assured.

Ingeborg also visited the well-known photography chain Sol Young, where she was photographed wearing a coat she cherished and wore with pride.

After living in New York and Chicago for more than seven years, Ingeborg decided to return to Norway to visit her parents and her two youngest siblings – especially because her father was in poor health. She was also curious to see the new house the family had built after she left.

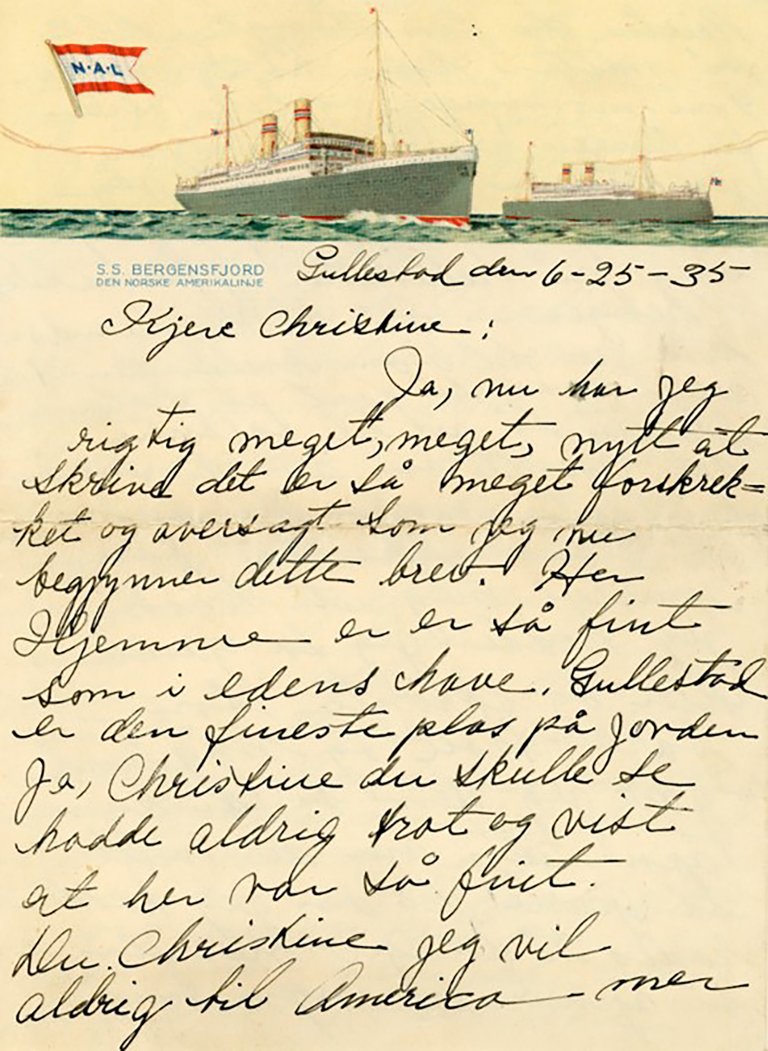

In June 1935, she boarded the Bergensfjord along with 510 other passengers, among them the writer Herman Wildenwey and his wife Gisken. During the crossing, Ingeborg got to know both of them, danced with Herman on the ship’s dance floor, and received a copy of his poetry collection Owls to Athens as a gift, inscribed with a personal dedication:

Miss Ingeborg Gullestad with the compliment of the author and best wishes. Bergensfjord 14th June 1935. Herman Wildewey.

In a letter to her sister Kristine, written shortly after returning home, Ingeborg described the journey as “very pleasant.” The weather had been so good that she was able to enjoy both the scenery and life aboard. When the ship docked in Bergen, she went ashore, rode the Fløibanen funicular, and ate at a restaurant – but she had a bit too much crab and pancakes, which made the rest of the journey to Stavanger less comfortable.

After arriving in Kristiansand, she continued her travels with all her luggage loaded into a kind of delivery truck. In Lyngdal, she switched to a private car, but her large travel trunk was left behind and sent the following day. Her brother Astor picked it up by horse.

Home again

In a letter to her sister Kristine, Ingeborg described what it felt like to return to Gullestad: "Here at home, it’s as beautiful as the Garden of Eden. Gullestad is the finest place on earth." She added that she would never go back to America – "not in a million years." She was deeply moved by how beautiful everything was and by how strongly she had longed for this place throughout her years abroad.

Yet the joy was tinged with sorrow. She was struck by how much her parents had aged and how her siblings had changed – especially her brother Astor, whom she barely recognized. Her homecoming became both a reaffirmation of belonging and a poignant reminder of how much time had passed since she left.

Excerpt from the Letter (1935)

Dear Christine,

I have so much to tell you – I hardly know where to begin. Home is as beautiful as the Garden of Eden. Gullestad is the finest place on earth. Oh, Christine, if only you could see it – you would never have believed it could be so lovely. Christine, I will never go back to America – not in a million years. All those years we dreamed of it, and now I know—this is paradise.

The voyage was wonderful. The weather was fine, and I wasn’t seasick the entire trip. We reached Bergen on the 20th at 5 o’clock. I went up on the Fløibanen funicular, ate at the restaurant there, and then visited several places around the city. The whole time in Bergen, I was out and about with a man from Seattle who claimed to know Ånen, Mama’s brother. We had such fun! The view from Fløibanen was beautiful – but not half as beautiful as Gullestad.

We left Bergen at 2 a.m. and arrived in Stavanger at 9 in the morning. The whole way from Bergen to Stavanger I was terribly sick because I had eaten crab and overindulged in pancakes in Bergen. Then on to Kristiansand—we arrived at 6 in the evening on the 21st. The weather was so fine, the sun shining. At customs they opened one of the small suitcases, but not the others. They just asked what I had, and I said “old clothes” and told a few tall tales. I gave them Nygland’s name so they could open it if they wanted. They asked if I had a radio, and I said, “Oh no!” – so they didn’t open anything.

Papa is not well – I hope you’ll get to see him at Christmas, and I mean that.

From Kristiansand I took a truck with all the luggage – it was quite nice. When I got to Lyngdal, I switched to a private car around midnight. I brought all the suitcases, but the big trunk stayed behind in Lyngdal. They sent it on the freight route the next day, Saturday. Astor fetched it with the horse. You can imagine the unpacking and sorting!

I was quite shocked when I saw Mama and Papa – they had grown so old. Christine, you should see them. And Astor is taller than Hans now! The first few days, when I spoke to Astor, I kept calling him Hans – it felt so strange, because he even sounds like Hans when he talks.

I’ll write again soon.

Ingeborg

A Sudden Loss

Just weeks after Ingeborg returned home, her mother died unexpectedly of heatstroke during the hay harvest. The loss affected the entire family and led Ingeborg to stay in Norway much longer than she had planned. Although she had written to her sister in excitement that she would never return to America, things turned out differently.

As time passed, it became clear that she would go back. She enjoyed life there, had good job opportunities, and friends and three siblings waiting for her. Her decision to return was an acknowledgment that she felt at home in two places, living very different lives in each.

A Proposal Before Departure

While still in Norway, she met Olav, who ran the first private secondary school in the area. His goal was to save enough money to attend university. He knew Ingeborg would soon return to America and had little to offer financially, but he asked for her hand just a week before her departure – hoping she would one day come back to Norway. Ingeborg hesitated to say yes, as she couldn’t promise she would return, but Olav said he was willing to take the chance.

Back to New York – and a New Crossroads

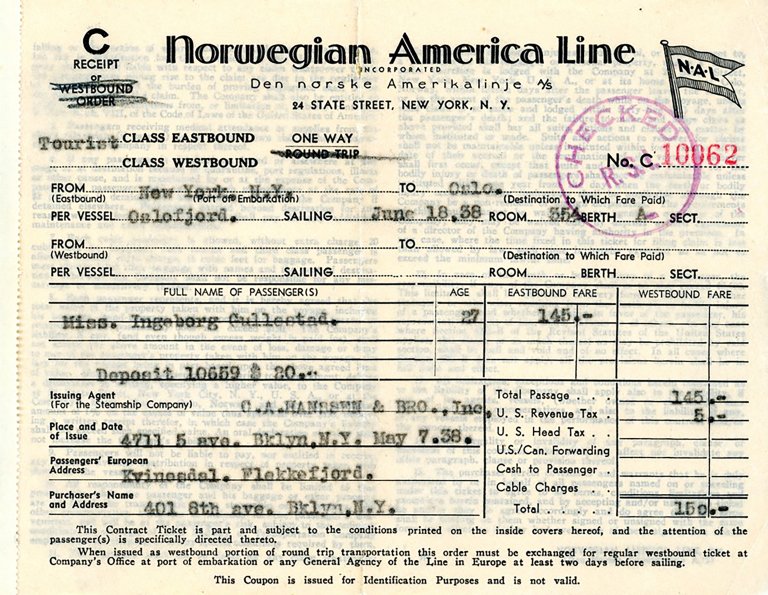

In May 1936, Ingeborg Gullestad returned to New York. She was listed as a dental technician, though she likely worked more as a secretary in a dental office. On her finger she wore the engagement ring she had recently – and somewhat hesitantly –accepted. During her first weeks back, she stayed with her brother Selmer and his family in Brooklyn.

Over time, she found work as a secretary at a doctor’s office, reconnected with friends and relatives, and enjoyed her leisure time. She was photographed both in the city – in parks and with friends – and on outings beyond it, including by a waterfall at Hålend Farm, a private rural property, in September 1937. Life in New York was social and active, and the thought of returning to Norway gradually faded.

One important reason was Ambrose Ryan, an Irish immigrant and police officer she had known for several years – actually long before she met Olav. They spent quite a bit of time together during her first stay in the United States, from 1928 to 1935, and reconnected when she returned in 1936. He had also arrived in New York in the late 1920s, and they shared the experience of being newcomers. Both often spoke about their families and the places they had left behind – Ingeborg about Norway, Ambrose about Ireland.

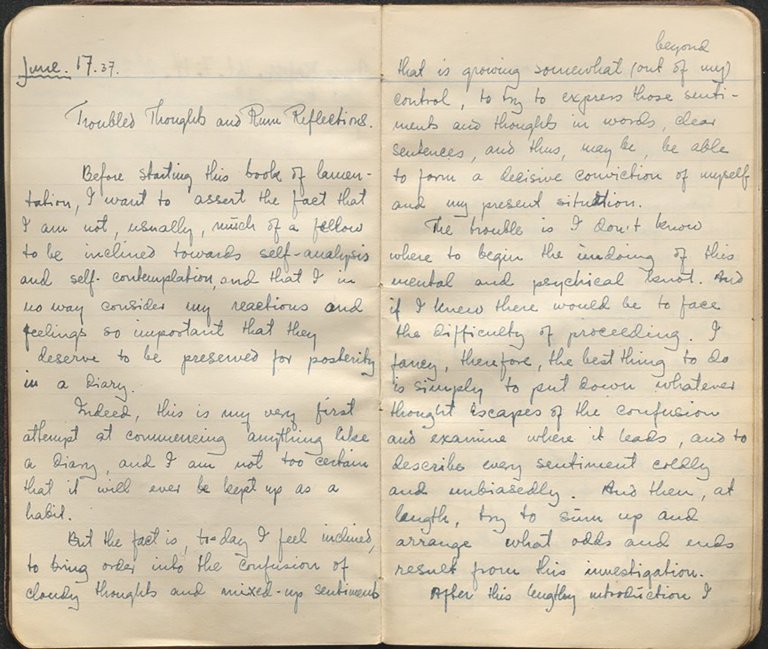

A Diary in Her Absence

While Ingeborg was building a life in America, Olav remained in Norway. Their daily routines were worlds apart – she was immersed in new ideas and social experiences in one of the world’s great cities, while his life was quieter, shaped largely by his work as a teacher. Ingeborg wasn’t as eager a letter writer as Olav, and weeks could pass without a reply.

In June 1937, Olav did something unusual: he began keeping a diary – and chose to write it in English. He titled it Troubled Thoughts and Rare Reflections. Perhaps it was his way of coping with uncertainty, or an attempt to feel closer to Ingeborg, who was still across the ocean.

He was restless and kept trying to figure out why. Was it the spring? Financial worries? Or something else?

The more he wrote, the clearer it became: what unsettled him most was missing Ingeborg. She hadn’t replied to his letters in over six weeks, and that made him uncertain. Did he truly love her? He asked himself the question directly – and tried to answer it as honestly as he could. He concluded that he did. Not just because he he missed her presence, but because he wanted to share his life with her: the conversations, the silences, the plans, the everyday moments.

The diary became a way to sort through his thoughts – and perhaps also a way to hold on to the hope that she was still thinking of him.

A Choice Between Two Lives

Eventually, Ingeborg confirmed that she was. She missed him – and life back home – more than she had allowed herself to admit. After two years, she decided to return for good.

She bought a white silk wedding dress and packed her suitcase. Just before leaving, she received a green jade ring from Ambrose. She had initially declined – after all, she was about to marry someone else – but Ambrose insisted: “Keep it as a memory.” The ring was a farewell gift.

Olav’s Diary

June 17.37

Troubled Thoughts and Rare Reflections.

Before starting this book of lamentation, I want to assert the fact that I am not, usually, much of a fellow to be inclined towards self-analysis and self- contemplation, and that I in no way consider my reactions and feeling so important that they deserve to be preserved for posterity in a diary.

Indeed, this is my very first attempt at commencing anything like a diary, and I am not too certain that it will ever be kept up as a habit.

But the fact is, today I feel inclined, to bring order into the confusion of cloudy thoughts and mixed-up sentiment that is growing somewhat (out of my) beyond control, to try to express those sentiments and thoughts in words, clear sentences, and thus, may be, be able to form a decisive conviction of myself and my present situation.

The trouble is I don’t know where to begin the undoing of this mental and psychical knot. And if I knew there would be to face the difficulty of proceeding. I fancy, therefore, the best thing to do is simply to put down whatever thought escapes of the confusion and examine where it leads, and to describe every sentiment coldly and unbiasedly. And the, at length, try to sum up and arrange what odds and ends result from this investigation.

After this lengthy introduction I feel I can pass on to registering my sundry ideas and impulses. First: What is the reason of my feeling so restless? Well, I may name a few:

- Spring-time. The coming of spring affects the glandular processes in my body, which in turn arouse certain passions, which in turn cause restlessness if not satisfied. Objection: I don’t feel, or seem not to feel, that those passions above mentioned are perceptibly different from what they were some months ago when I had no worry about restlessness.

- Economical stress. The inability of paying my income tax and mortgages causes uncertainty of the future which, subconsciously develops restlessness. Objection: Would this restlessness disappear the moment I had sufficient means to meet my obligations? Anyhow, my lack of money is only temporary and has bearing only upon the immediate future, it will pass away, and then I shall have sufficient funds.

- Inge’s failing to answer my letters. It’s here I think the real cause of the trouble is. In order to get sure I want to investigate further into this subject.

- Do I really love her?

An honest answer to such a question sometimes is, in most cases, beyond a man’s power. As far as I can see there has not yet been given a clear definition of the word love, and, I think, never will. It is a feeling, based on physical and psychical phenomena, and of its existence or non-existence, it seems to me, nothing can be concluded but from the presence resp. absence of a desire to enjoy the company of the object of love.

I am aware that the presence of such a desire is no certain indication of the special sort of love supposed to exist between engaged and married people. It may also indicate friendship, thoughtfulness or, simply. Loneliness of the part cherishing this desire.

It seems as though this desire must have some special characteristics from which to conclude it arises out of love. It will have to be more of a passion than ordinary longing, it will have to be focused on one person in particular, and not on human company in general, to be mingled with certain physical and psychical emotions only experienced toward an object of love.

Well, to avoid losing track in a tangle of inadequate and incomplete philosophical phrases, let me turn back to my own special case. How do I feel? What do I want? I want her company. Her kiss. Her embraces. I want to kiss her, squeeze her, spend the nights with her. Don’t I feel that way towards other women? No, not exactly. They may arouse momentary passions, but I know I would be ashamed of myself if those passions were allowed to be satisfied. It’s different with her. It would seem the natural thing, clear, honest.

I want to have talks with her, go hiking with her, sit at the fire of an evening saying nothing in her company, share my joys and sorrows with her, show her things I think beautiful. I shouldn’t be sky in her company. I should confide to her my plans for the future, discuss them with her, ask her advice and seek her approval. And in her presence I shouldn’t give myself airs of being anything more than I am in order to maintain my social position, but to make her respect me, love me.

After which I think I can justly say I love her.

- It is natural that the lack of correspondence on her part should create restlessness on mine? Yes. Love, naturally, is contented only if the other part makes clear it is reciprocated. The faintest suspicion of indifference makes one agitated and anxious. And that is all there is to it, I feel. I love her, anxious about her, bring for her letters of which I have had none for ever so long, for more that six weeks. No wonder I am feeling touchy, sentimental, those things I always used to despise.

Well, but didn’t you lead this examination where you wanted it? Didn’t you form the questions so as anticipate the answers you wanted?

May be. I know it is impossible to make a thoroughly impartial, objective, unbiased opinion of oneself. But, that granted, suppose I managed to trick myself into believing I had found an irrefutable proof of my love to Inge, does not the whole investigation, even my faking it the way I did, does it not, I ask, show to the world more brilliantly that any impartial, unprejudiced judgement – that I love her?

18. juni 37 continued

Last night M. produced three bottles of wine, our gang were summoned and the carouse was held in Agnes’ room. We played the gramophone, told smoothly stories and cracked daring jokes when Agnes said she wanted me to go with her to make hay at her farm up in the mountains.

Per started playing, ‘The Music Goes round’ and before long he was dancing in the midst of the room, twisting and bending like a worm. Suddenly he pulled his shirt of his trousers showing us his little belly. Agnes was horrified, pushed him away, he was stubborn and wanted keeping on. At last she joined him in the dance, both twisting and wriggling and dancing their shirt and blouse up as far as possible. Inga foamed with rage at her sister’s indecency. Later in the day. No letter. And I’m getting angry. I think I’ll go over to Gullestad for a couple of hours.

On June 18, 1938, Ingeborg left America – and Ambrose Ryan – behind to begin a life in Norway with Olav Fintland.

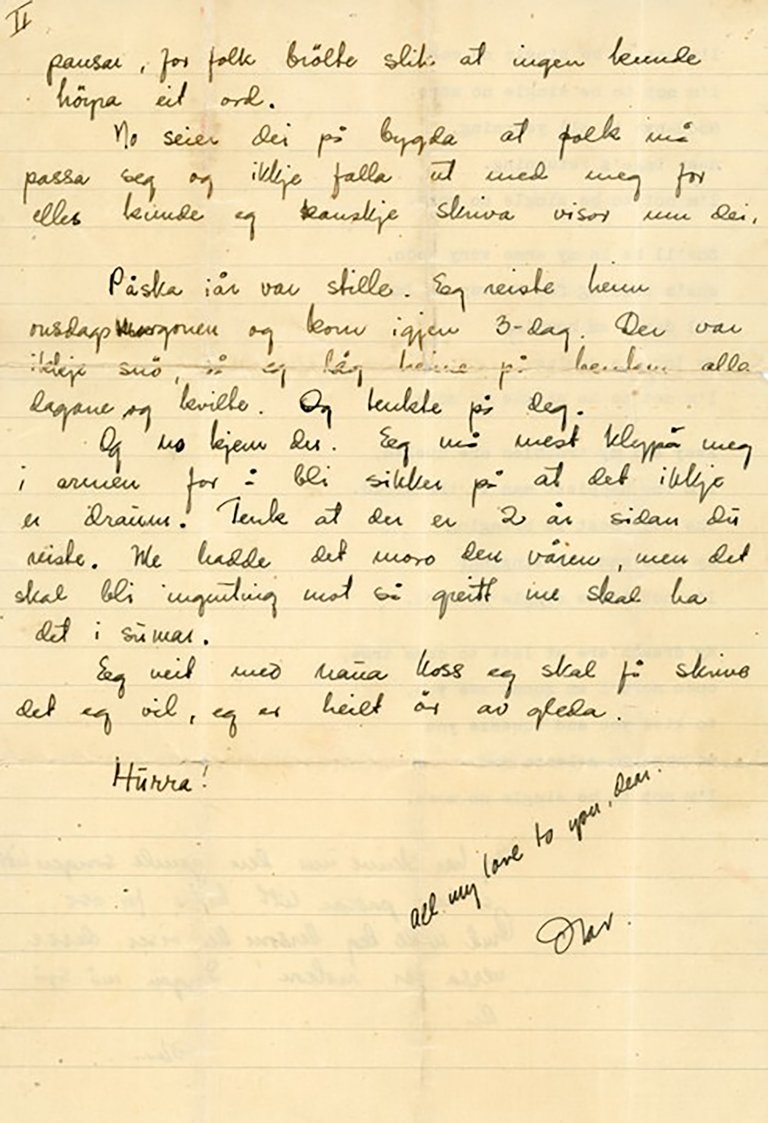

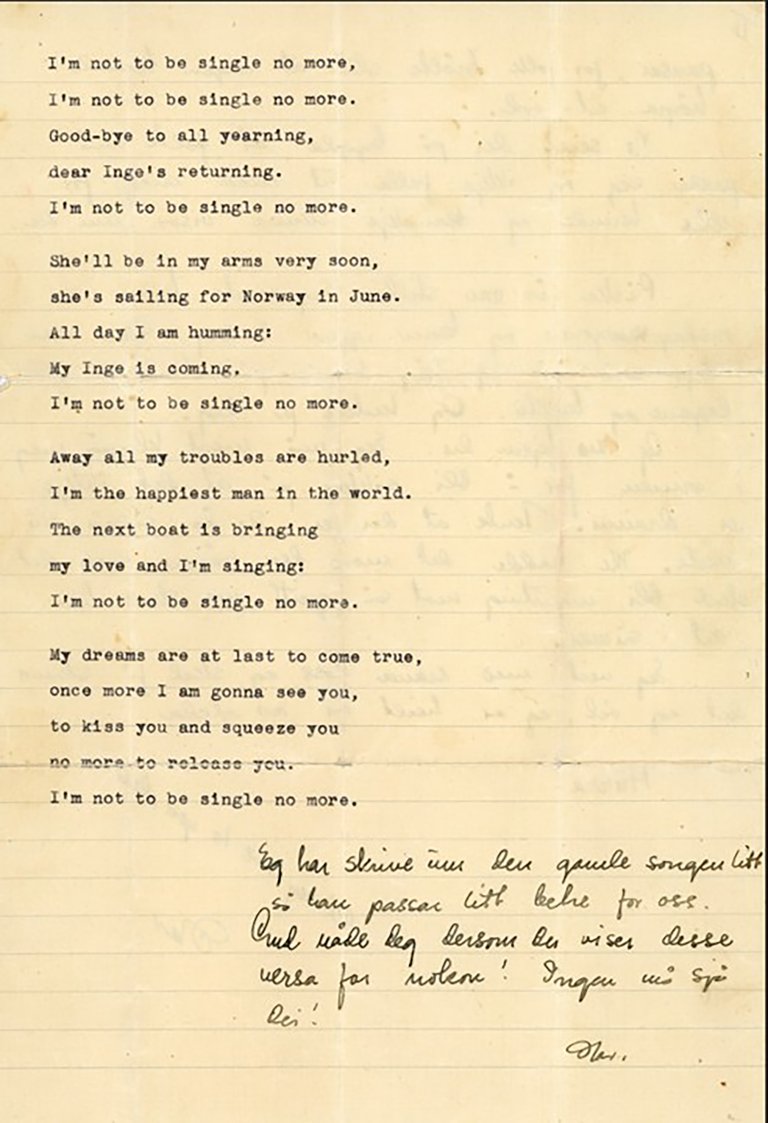

Olav was overjoyed. In the last letter he sent before Ingeborg was due to travel, he wrote:

Easter was quiet this year. I went home Wednesday morning and returned on the third day. There was no snow, so I lay on the bench at home each day and rested. And thought of you.

And now you’re coming. I almost have to pinch myself to be sure it’s not a dream. Imagine – it’s been two years since you left. We had fun that spring, but it will be nothing compared to how good this summer will be.

I hardly know how to write what I want to say – I’m dizzy with joy. Hurrah! All my love to you, dear. Olav

On New Year’s Eve 1938, Ingeborg wore the white silk wedding dress she had bought in New York, and the wedding was celebrated at the Gullestad family farm.

Ingeborg Gullestad’s story offers a personal and unique insight into how a single life story can illuminate the experience of a Norwegian emigrant in 1930s America. Her photographs present a version of the American Dream, portraying a woman who was discerning, sociable, adaptable, and optimistic.

The images offer a different perspective on migration history than what we typically find in textbooks. They bring one individual’s journey to life and remind us that history is also shaped by close and personal stories.

The exhibition was created by Ine Fintland (Senior Archivist and granddaughter of Ingeborg Gullestad) and Synnøve Østebø (Archivist).

We received valuable assistance from Almina Jazavac (Higher Executive Officer), Rebekka Rostrup (Senior Adviser), Hanne Karin Sandvik (Senior Adviser), Eivind Skarung (Senior Adviser), and Sissel Eltvik Wang (Senior Adviser).

The article was originally written in Norwegian and translated into English using Copilot, based on the prompt: “Translate idiomatically for an American audience. The article will be published on the website of the National Archives of Norway. Use terminology appropriate for a U.S. readership, and ensure the language is clear and concise.” The final version was reviewed and edited by Ine Fintland and Janet B. Martin (Senior Advisor) for clarity and accuracy.